I have looked at country risk, in all its dimensions, towards the middle of each year, for the last decade, for many reasons. One is curiosity, as political and economic crises roll through regions of the world, roiling long-held beliefs about safe and risky countries. The other is pragmatic, since it is almost impossible to value a company or business, without a clear sense of how risk exposure varies across the world, since for many companies, either the inputs to or their production processes are in foreign markets or the output is outside domestic markets. Coca Cola is a US company, in terms of history and incorporation, but it generates a significant portion of its revenues from the rest of the world. Royal Dutch may be a UK (or Dutch) company, in terms of incorporation and trading location, but it extracts its oil and gas from some of the riskiest parts of the world. Since country risk is multidimensional and dynamic, my annual country risk update runs to more than a hundred (boring) pages, but I will try to summarize what the last year has brought in this post.

Drivers of Country Risk

What makes some countries riskier than others to operate a business in? The answer is complicated, because everything has an effect on risk, starting with the political governance system (democracy, dictatorship or something in between), the extent of corruption in the system, the legal system (and its protection for property rights) and the presence or absence of violence in the country (from wars within or without). The table below, which I have used in prior updates, captures the mail drivers of country risk:

1. Democracy across the Globe

If your focus stays on economic risk, the question of whether democracies or authoritarian regimes are less risky for businesses to operate in depends in large part on whether these businesses are more unsettled by day-to-day continuous risk, which is often the case with democracies, where the rules can change when new governments gets elected, or by discontinuous risk, which can lie dormant for long periods, but when it does occur, it is larger and sometimes catastrophic, in an authoritarian government. Assessing freedom and democracy in countries is a fraught exercise, with both political and regional biases playing out, and that should be kept in mind when you look at the heat map that shows the results of the Economist's measures of democracy, by country and region, in 2022, as well as trend lines across time:

|

| Source: Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) |

In my view, the question of whether businesses prefer the continuous change (or, in some cases, chaos) that characterizes democracies or the potential for discontinuous and sometimes jarring change in authoritarian regimes has driven the debate of whether a business should feel more comfortable investing in India, a sometimes chaotic democracy where the rules keep changing, or in China, where Beijing is better positioned to promise continuity. For three decades, China has won this battle, but in 2023, the battleground seems to be shifting in favor of India, but it is still too early to make a judgment on whether this is a long term change, or just a hiccup.

2. Violence across the Globe

When a country is exposed to violence, either from the outside or from within, it not only exposes its citizens to physical risk (of assault or death), but also makes it more difficult to run businesses within its borders. That risk can show up as costs (of buying protection or insurance) or as uninsurable risks that drive up the rates of return investors and businesses need to make, in order to operate. Again, there are subjective judgments at play in these measures, but the map below gives you 2023 scores for peace scores, with lower (higher) scores indicating less (more) exposure to violence.

|

| Source: Vision of Humanity |

3. Corruption across the Globe

Corruption is a social ill that manifests itself as a cost to every business that is exposed to it. As anyone who has ever tried to get anything done in a corrupt setting will attest, corruption adds layers of costs to routine operations, thus become an implicit tax that companies pay, where the payment instead of going to the public exchequer, finds its way into the pockets of intermediaries. Transparency International measures corruption scores, by country, across the world and their 2022 measures are in the map below:

|

| Transparency International |

4. Legal Protection across the Globe

To operate a business successfully, you need a legal system that enforces contractual obligations and protects property rights, and does so in a timely manner. When a legal system allows contracts and legal agreements to be breached, and property rights to be violated, with no or extremely delayed consequences, the only businesses that survive will be the ones run by lawbreakers, and not surprisingly, violence and corruption become part of the package. The Property Rights Alliance measures the protection offered for property rights (intellectual, physical), with higher (lower) scores going with better (worse) protection, and their most recent update (from 2022) is captured in the picture below:

|

| Source: Property Rights Alliance |

By now, you can see the point about the correlation across the various dimensions of country risk, with the parts of the world (North America, Europe, Australia and Japan) that have the most democratic systems and the least corruption scoring highest on the legal protection scores. Conversely, the regions (Africa, large portions of Asia and Latin America) that are least democratic, with the most violence and corruption, have the most porous legal systems.

Measures of Country Risk

With the long lead in on the dimensions of country risk, we can now turn to the more practical question of how to convert these different components of risk into country risk measures. We will start with a limited measure of the risk of default on the part of governments, i.e., sovereign default risk, before expanding that measure to consider other country risks, in political risk scores.

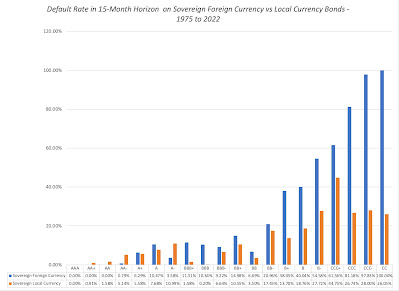

1. Default Risk

Businesses and individuals that borrow money sometimes find themselves unable to meet their contractual obligations, and default, and so too can governments. The difference is that government or sovereign default has much greater spillover effects on all entities that operate within its borders, thus creating business risks. We start with an assessment of sovereign ratings, a widely accessible and hotly contested, of government default risk and then move on to market-based measures of this risk in the form of sovereign default spreads.

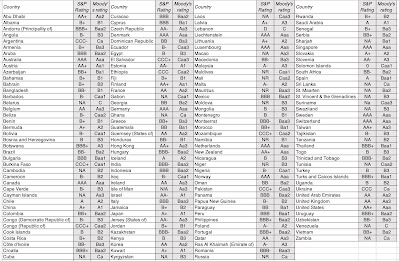

a. Sovereign Ratings

The most widely used measures of sovereign default risk come from a familiar source for default risk measures, the ratings agencies. S&P, Moody's and Fitch, in addition to rating companies for default risk, also rate governments, and they rate them both on local currency debt, as well as foreign currency debt. The reason for the differentiation is simple, since countries should be less likely to default, when they borrow in their domestic currencies, than when they borrow in a foreign currency. The table below summaries the sovereign local currency ratings for countries in June 2023, from S&P and Moody's:

b. Sovereign CDS Spreads

One of the advantages of a market-based measure is that the market price reflects investor perceptions of risk at the moment. Sovereign Credit Default Swaps (CDS) offer a market-based measure of default risk, since investors buy these swaps as protection against default on government bonds. When the sovereign CDS market came into being a few decades ago, there were only a handful of countries that were traded, but the market has expanded, and there are traded credit default swaps on almost 80 countries in June 2023. The graph below shows the sovereign CDS levels, by country:

|

| Source: Bloomberg (July 2023 data) |

2. Risk Scores

The advantage of default spreads is that they provide an observable measure of risk that can be easily incorporated into discount rates or financial analysis. The disadvantage is that they are focused on just default risk, and do not explicitly factor in the other risks that we enumerated in the last section. Since these other risks are so highly correlated with each other, for most counties, it is true that default risk becomes an reasonable proxy for overall country risk, but there are some countries where this is not the case. Consider portions of the Middle East, and especially Saudi Arabia, where default risk is not significant, since the country borrows very little and has a huge cash cushion from its oil reserves. Investors in Saudi Arabia are still exposed to significant risks from political upheaval or unrest, and may prefer a more comprehensive measure of country risk.

There are many services, including the World Bank and the Economist, who offer comprehensive country risk scores, and the map below includes composite country risk scores from Political Risk Services in June 2023:

Equity Risk across Countries

Default risk measures how much risk investors are exposed to, when investing in bonds issued by a government, but when you own a business, or the equity in that business, your risk exposure is not just magnified, but also broader. For three decades, I have wrestled with measuring this additional risk exposure and converting that measurement into an equity risk premium, but it remains a work in progress.

To estimate the equity risk premium, for most countries I start with default spreads, either based on the sovereign ratings assigned by the ratings agencies, or from the market, in the form of sovereign CDS spreads. To account for the fact that equities are riskier than bonds, I scale the standard deviation of an emerging market equity index (S&P Emerging BMI) to an emerging market government bond ETF (iShares JPM USD Emerging Markets Bond ETF), and use this ratio (1.42 in my July 2023 update) and apply this scalar to the default spread, to arrive at a country risk premium. Adding that country risk premium on to the premium that I estimate for the S&P 500 (which was 5.00% at the start of July 2023, and is my measure of a mature market premium), yields the total equity risk premium for a country:

|

| Download spreadsheet with data |

Caveats and Questions

I started publishing equity risk premiums about 30 years ago, and while data sources have become richer and more complete, the core approach that I use for the estimation has remaining stable. That said, there is no intellectual firepower or research behind these numbers, since I am letting the default ratings agencies and risk measurement services carry that weight. I am not a country risk researcher, and I try not to let my personal views alter the numbers that emerge from the analysis, since that would open the door to my biases. I will use three countries in the latest update to illustrate my point:

- Saudi Arabia: As I noted earlier, using default spreads as my starting point can result in understating the risk premium for countries like Saudi Arabia, which score low on default risk but high on other risks.

- Libya: As indicated in the last section, the equity risk premium for Libya, an unrated country, is entirely based upon the country risk score from PRS. That country risk score is surprisingly high (indicating low risk) and it results in an equity risk premium that is low, relative to other countries in the region.

- China: China has a high sovereign rating and a low sovereign CDS spread, indicating that investors in Chinese government bonds don't see much default risk in the country. In the aftermath of a Beijing crackdown on Chinese tech giants and talk of a trade war between China and the US, the perception seems to be that China has become a riskier place to invest. That may or may not be true, but looking at how Chinese equities are priced, trading still at some of the highest multiples of earnings in the world, investors in equity markets don't seem to share that view.

This post has already become much longer than I intended it to be, but I want to end by bringing these equity risk premiums down to the company level, and examining how they play out in hurdle rates, to be used in investment analysis by companies and valuation by investors.

The Currency Question

In my discussion so far, you will notice that I have stayed away from talking about currency risk in my equity risk premium discussion and from currency choices in investment analysis. I have my reasons.

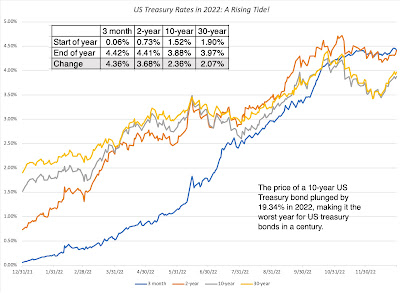

- I know that the currency choice is the source of angst for many analysts, and I think unnecessarily so. Your choice of currency will affect your cash flows and your discount rates, but only because each currency brings it's own expectations of inflation, with higher inflation currencies leading to higher growth rates for cash flows and higher discount rates.The mechanism that allows for the discount rate adjustment to reflect currency is the risk free rate, with currencies with higher expected inflation carrying higher risk free rates. In a downloadable dataset linked at the end of this post, I estimate riskfree rates in global currencies, based upon the US T.Bond rate as the riskfree rate in US dollars) and differential inflation. To provide an example, using the IMF's estimate of expected inflation for 2023-28 of 3% for the US and 13.50% for Egypt, and building on the US treasury bond rate of 3.80%. the riskfree rate in Egyptian pounds is 14.38%.Riskfree Rate in EGP = (1+ US T.Bond Rate) (1 + Exp Infl in Egypt) (1+ Exp Infl in US) -1

= (1.038)* (1.135/1.03) -1 = .1438 or 14.38%)

- To the extent that currency risk adds to the operating risk of a company, it is, in my view, already embedded in the equity risk premiums that I have computed in the last section. After all, countries with unstable governments, plagued by war and corruption, also have the most unstable currencies. The other reason to tread lightly with currency risk is that for investors with global portfolios, it becomes diversifiable risk, as some companies benefit as a currency strengthens or weakened more than expected and others lose for exactly the same reason.

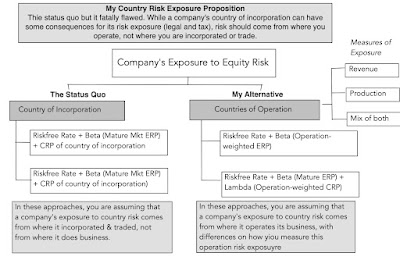

Exposure to Country Risk

For much of my valuation journey, the status quo in valuation has been to look at where a company is incorporated to determine its risk exposure (and the equity risk premium to use in assessing a hurdle rate). While I understand that where you are incorporated and traded can have an effect on your risk exposure, I think it is dwarfed by the risk exposure from where you operate. A company that is incorporated in Germany that gets all of its revenues in Turkey, is far more exposed to the country risk of Turkey than that of Germany. In the picture below, I contrast the traditional country-of-incorporation based risk measure with my alternative, where equity risk premiums come from where you operate:

Conclusion

It is ironic that a post that was meant to shorten and summarize a long paper has itself stretched to become the equivalent of a long paper, and I apologize. I do hope that you get a chance to read the paper or at least review my country risk measures in this post, since there is significant room for improvement. I don't have all the answers, and I probably never will, but progress is incremental, and each year, I hope that I can add a tweak or a component that will move me in the right direction. Also, please don’t take any of these numbers personally. In short, if you feel that I have overestimated the risk in your country and given it an equity risk premium that you believe is undeservedly high, it is not because I do not like you and your country. It is entirely Moody’s fault for giving your country too low a rating, and you should take it up with them!

YouTube Video

Country Risk Paper

Country Risk Data

- Democracy, Violence, Corruption and Legal System Scores, by Country, in July 2023

- Sovereign Ratings and CDS Spreads for Countries in July 2023

- Equity Risk Premiums, by Country, in July 2023