Last year, I wrote a post on ESG and explained why I was skeptical about the claims made by advocates about the benefits it would bring to companies, investors and society. In the year since, I have heard from many on the topic, and while there are some who agreed with me on the internal inconsistencies in its arguments, there were quite a few who disagreed with me. In keeping with my belief that you learn more by engaging with those who disagree with you, than those who do, I have tried my best to see things through the eyes of ESG true believers, and I must confess that the more I look at ESG, the more convinced I become that "there is no there there". More than ever, I believe that ESG is not just a mistake that will cost companies and investors money, while making the world worse off, but that it create more harm than good for society.

ESG: Value and Pricing Implications

Rather than repeat in detail the points I made in last year's post, I will summarize my key conclusions, with addendums and modifications, based upon the feedback (positive and negative) that I have received.

1. Goodness is difficult to measure, and the task will not get easier!

The starting point for the ESG argument is the premise that we can come up with measures of goodness that can then be targeted by corporate managers and used by investors. To meet this demand, services have popped up around the world, claiming to measure ESG with scores and ratings. As I noted in my last post, there seems to be little consensus across services on how to measure goodness, and the low correlation across service measures of ESG has been well chronicled. The counter from the ESG services and ESG advocates is that these differences reflect growing pains, and just as bond ratings agencies found convergence on measuring default risk, services will also find commonalities. I think that view misses a key difference between default risk and goodness, insofar as default is an observable event and services were able to learn from corporate defaults and fine tune their ratings. Goodness is in the eyes of the beholder, and what you perceive to be a grevious corporate sin may not even register on my list, as a problem. To illustrate how investors can differ on core values, consider the chart below, where investors were asked to assess which issues should rank highest, when considering corporate goodness:

Based on this survey, younger investors want the focus to be on global warming and plastics, whereas older investors seem to focus on data fraud and gun control. If you expand these factors to include other social and religious issues, I would wager that the differences will only widen. As ESG scores and ratings get more traction, researchers are also looking at the factors that allow companies to get high scores and good rankings, and improve them over time. Studies of ESG scores find that they were influenced by company size and location, with larger companies getting higher ESG scores/rankings than smaller companies, and developed market companies getting higher scores and rankings than emerging market companies:

|

| LaBella, Sullivan, Russel and Novikov (2019) |

It is entirely possible that big companies are better corporate citizens than smaller ones, but it is also just as plausible that big companies have the resources to play the ESG scoring game, and that more disclosure is a tactic used by these companies that want to bury skeletons in their current or past lives, rather than expose them. In fact, a JP Morgan study of ESG Ratings and disclosures also points to a larger danger from enhanced ESG disclosure requirements, which is that the ESG ratings seems to increase across companies, as disclosure increase.

|

| Chen et al, JP Morgan |

While I am sure that there will be some in the ESG community who will view this as vindication that disclosure is inducing better corporate behavior, the cynic in me sees companies learning to play the ESG game, at least as designed by services, and using the disclosure process to check boxes and up their scores. To me, the parallels to the corporate governance movement from two decades ago are uncanny, where services rushed to estimate corporate governance scores for companies, accountants and rule writers added hundreds of pages of disclosure on corporate governance, and promises were made of a "golden age" for shareholder power. The fact that the corporate governance movement enriched services, consultants and bankers, and left shareholders more powerless than they were before the movement started, holding shares in companies with dual class shares or worse, should act as a warning for ESG disclosure/measurement advocates, but I have a feeling that it will not.

2. Being “good” will add to value some companies, hurt others, and leave the rest unaffected!

3. The ESG sales pitch to investors is internally inconsistent and fundamentally incoherent

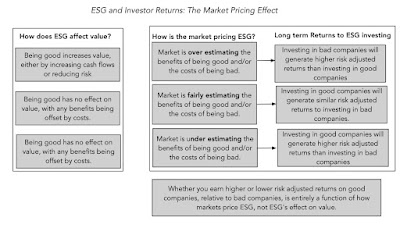

If the argument that ESG translates into higher value is weak, the argument that incorporating ESG into your investing is going to increase your returns fails a very simple investment test. For any variable, no matter how intuitive and obvious its connection to value might be, to generate "excess" returns, you have to consider whether it has been priced in already. That is why investing in a well managed company or one that has high growth does not translate into excess returns, if the market already is pricing in the management and growth. Applying this principle to ESG investing, the question of whether ESG-based investing pays off or not depends on not only whether you think ESG increases or decreases firm value, but also on whether the market has already priced in the impact.

- If the market has fully priced in the ESG effect on value, positive or negative, investing in 'good' companies or avoiding 'bad' companies will have no effect on excess returns. In fact, if being good makes companies less risky, investors in good companies will earn lower returns than investors in bad companies, before adjusting for risk, and equivalent returns after adjusting for risk.

- If the market is over enthused with ESG and is overpricing how much being "good" will add to a company's profitability or reduce risk, investing in 'good' companies will generate lower risk-adjusted returns than investing in 'bad' companies.

- If the market is underestimating the benefits of being good on growth, margins and risk, investing in 'good' companies will generate higher returns for investors, even after adjusting for risk.

- The first is that it suggests that much of the research on the relationship between ESG and returns yields murky findings. Put simply, there is very little that we learn from these studies, whether they find positive or negative relationships between ESG and investor returns, since that relationship is compatible with a number of competing hypotheses about ESG, value and price.

- The second is that bringing in market pricing does shed some light on perhaps the only aspect of ESG investing that seems to deliver a payoff for investors, which is investing ahead or during market transitions. In my last post, I pointed to this study that find that activist investors who take stakes in "bad" companies and try to get them to change their ways generate significant excess returns from doing so. Another study contends that investing in companies that improve their ESG can generate excess returns of about 3% a year, but skepticism is in order because it is based upon a proprietary ESG improvement score (REIS), and was generated by an asset management firm that invests based upon that score.

4. Outsourcing your conscience is a salve, not a solution!

Even if being “good” does not increase value or make investors better off, could it still help, by making the world a better place? After all, what harm can there be in asking and putting pressure on companies to behave well, even if costs them? In the short term, the answer may be no, but in the long term, I believe that this will cost us all (as society). The ESG movement has given each of us an easy way out of having to make choices, by outsourcing these choices to corporate CEOs and investment fund managers, asking them to be “good” for us, while not charging us more for their products and services (as consumers) and delivering above-average returns (as investors). Implicit in the ESG push is the presumption that unless companies that are explicitly committed to ESG, they cannot contribute to society, but that is not true. Consider Bill Gates and Warren Buffett, two men who built extraordinarily valuable companies, with goodness a factor in decision making only if it was good for business. Both men have not only made giving pledges, promising to give away most of their wealth to their favorite causes in their lifetimes, and living up to that promise, but they have also made their shareholders wealthy, and many of them give money back to society. As I see it, the difference between this “old” model of business and the proposed “new ESG” version is in who does the giving to society, with corporate CEOs and management taking over that responsibility from shareholders. I am willing to listen to arguments for why this new model is better, but I am certainly not willing to concede, without challenge, that a corporate CEO knows my value system better than I do, as a shareholder, and is better positioned to make judgments on how much to give back to society, and to whom, than I am.

For a perspective more informed and eloquent than mine, I would strongly recommend this piece by Tariq Fancy, whose stint at BlackRock, as chief investment officer for sustainable investing, put him at the heart of the ESG investing movement. He argues that trusting companies and investment fund managers to make the right judgments for society will fail, because their views (and actions) will be driven by profits, for companies, and investment returns, for fund managers. He also believes that governments and regulators have been derelict in writing rules and laws, allowing companies to step into the void. While I don’t share his faith that government actions are the solution, I share his view that entities whose prime reasons for existence are to generate profits for shareholders (companies) or returns for investors (investment funds) all ill suited to be custodians of public good.

Cui Bono? The ESG Gravy Train (or Circle)!

If ESG is a flawed concept, perhaps fatally so, and if the flaws are visible for everyone to see, how do we explain the immense push in both corporate and investment settings? I think the answer always lies in asking the question "Cui Bono, or who benefits?". With ESG, the answer seems to be everyone, but those it is purported to help, i.e. corporate stakeholders, investors and society. The picture below captures the groups that have primarily benefited from the ESG boom, and how they feed off each other.

Given how much ESG disclosure advocates, measurement services, investment funds and consultants feed off each other, it is no wonder that they have an incentive to sell you on its unstoppable growth and inevitable success. Given that shareholders in companies and investors in funds are paying for this gravy, you may wonder why corporate CEOs not only go along with this charade, but also actively encourage it, and the answer lies in the power it gives them to bypass shareholders and to evade accountability. After all, these are the same CEOs who, in 2019, put forth the fanciful, but great sounding, argument that it is a company’s responsibility to maximize stakeholder wealth, rather than cater to shareholders, which I argued in a post then that being accountable to everyone effectively meant that CEOs were accountable to no one. In some cases, flaunting goodness has become a way that founders and CEOs use to cover business model weaknesses and overreach. It is a point that I made in my posts on Theranos, at the time of its implosion in October 2015, and on WeWork, during its IPO debacle in 2019, noting that Elizabeth Holmes and Adam Neumann used their “noble purpose” credentials to cover up fraud and narcissism.

A Roadmap for being and doing Good

My skepticism about ESG notwithstanding, I understand its draw, especially on the young. As individuals, each of us has a moral code, sometimes coming from religion, sometimes from family and sometimes from culture, but whatever its source, our actions should be consistent with that code. Since those actions involve what we do at work, and in investing, it stands to reason that there are some investments you will and should not make, because it violates your sense of right and wrong, and other investments that you will make, because they advance your view of goodness. It is for this reason that I would suggest a more nuanced and personalized version of ESG, built around the following principles:

- Start with a personalized measure of goodness, and don’t overreach: The key with moral codes is that they are personal, and for goodness to be incorporated into your investment and business decisions, you have to bring in your value judgments, rather than leave it to ESG measurement services or to portfolio managers. I would also recommend that you focus on core values, rather than try to find a match on every one, not only because adding too restrictions will constrain you in your choices, perhaps to the point of paralysis, but also because you may find yourself accepting major compromises on your key values in order to meet secondary values.

- As a business person, be clear on how being good will affect business models and value: If you own a business, you are absolutely within your rights to bring your personal views on morality into your business decisions, but if you do so, you should work through the effects on growth, margins and risk, and be at peace with the fact that staying true to your values may, and probably will, cost you money. If you are making decisions at a publicly traded company, as an employee, manager or even CEO, you are investing other people’s money and if you choose to make decisions based upon your personalized moral code, you cannot justify these decisions with hand waving and double talk. In fact, you have an obligation to be open about what your conscience will cost your shareholders, a twist on disclosure that ESG advocates will not like.

- As an investor, understand how much goodness has been priced in: If you are an investor, you don’t have to compromise on your values, as long as you start with the recognition that, at least in the long term, you will have to accept lower returns than you would have earned without that constraint. If you are tempted to have your cake and eat it too, and who isn’t, you may be able to do so by getting ahead of the market in detecting shifts in social mores and pushing for change in the companies you invest in, to change.

- As a consumer and citizen, make choices that are consistent with your moral code: If you believe that owning a portfolio of “good” stocks or running a “good” business is all you have to do to fulfill your moral or societal obligations, you are wrong. Your consumption decisions (on which products and services you buy) and your citizenship decisions (on voting and community participation) have as big, if not greater, an effect. Put simply, if your key societal issue is climate change, your refusal to own fossil fuel stocks in your portfolio is of little consequence, if you still drive a gas guzzler, air condition your house to feel like an ice box all summer and take private corporate jets to Davos every year.