I wrote about my most recent valuation of Tesla just over a week ago, and as has always been the case when I value this company, I have heard from both sides of the Tesla divide. Some of you believe that I am being far too generous in my forecasts of revenues and profitability for a company that is facing significant competition, as it pursues growth, especially with questions about who's in charge of the company. Others, just as passionately, have argued that I am under estimating the company's capacity to grow, enter new businesses and generate additional profits, and have pointed to my history of undershooting with the company. I am not defensive about my valuations, and am completely unfazed by the pushback, but I do think that since some of the pushback revolves around first principles of intrinsic value, rather than specifics about the company, there is value in discussing the issues raised.

My Tesla Valuation: Filling in the Missing Pieces

When I posted my Tesla valuation, I hoped, perhaps naively, that it would be self-standing, with the combination of the valuation picture and the spreadsheet filling in the details. Based at least on the reactions, I have realized that some may be misreading my story and valuation, ore reacting just to a picture in a tweet. To fill in the missing pieces, I redid the valuation picture, adding the revenue growth rate, by year:

|

| Download spreadsheet |

- First, the revenue growth rate, at least for me, is a means to an end, not an end in itself. A few of you did take issue with the fact that the growth rate that I used for the first five years dropped from 35%, in my November 2021 valuation, to 24%, in my most recent one. That may seem like a negative reassessment of the company, but growth rates can deceptive as companies get larger, and my revenues in 2032 in both valuations converge on almost exactly the same number ($420 billion in November 2021 valuation and $412 billion in this one). Just to provide perspective, using a 35% growth rate now would inflate revenues to $600 billion in 2032 or higher, requiring a very different narrative for the company.

- Second, as you get past year 5, the revenue growth rate does not drop precipitously to 3.47% in year 6 (more on that in the next bullet), and instead declines, in linear terms, between years 6 and 10 to approach 3.47% in 2032. In short, the company has ten years of growth, not five, but growth rates have to get smaller as revenues gets bigger.

- Third, if it is what happens after year 10 that puzzles you, it has less to do with Tesla the company and more to do with answers to two questions. The first of the is as companies scale up, there will be a point where they will hit a growth wall, and their growth will converge on the growth rate for the economy. The second is the question of what the nominal growth in the global economy, in US dollar terms, will be, and my best answer to that question is the nominal risk free rate, which was 3.47% at the time of this valuation. I am assuming that Tesla will hit its growth wall at about $400 billion in annual revenues, but as I will note in the next section, that can be debated, but the growth rate forever is bound by mathematical constraints to override.

- Fourth, on my operating margin assumptions, it does look like I am downbeat about the near future, since my operating margin is dropping from 17.93% to 16% over the next five years, but that is because the former is the operating margin during 2022, and the number careened wildly during the course of the year from more than 19% in the first quarter of the year, to just about 16% in the last quarter. In short, I am assuming that the price cuts and cost pressures of the fourth quarter are more representative of what Tesla will face in the future, as competition steps up.

- Finally, my starting cost of capital of 10.15% reflects the reality that the riskfree rate and equity risk premiums have risen over 2022, and my ending number of 9% is an indication that I expect Tesla to become less risky over time. There is not much room to maneuver on either number, since half of all US companies have costs of capital between 7.3% and 10.9%.

In short, my value of $130/share reflects the confluence of these assumptions, and as I conceded, I can and will be wrong on each of them.

The Pushback

I must confess that I have not read every single comment and critique of my valuation, since they are dispersed over multiple platforms, but I do know that the pushback has come from both sides. There are Tesla bulls who are convinced that I am understating its value, and Tesla bears, who are just as convinced that I am overstating its value. Some of the reasons provided are substantive, and merit serious debate, others reflect a serious misreading of intrinsic valuation and a few are just assertions, with nothing to debate.

From Tesla Bulls

Given that I found Tesla to be overvalued, albeit only mildly, about three quarters of the disagreements posted online to the valuation came from Tesla bulls, some of whom have disagreed with me for a decade, and have, for the most part, been on the right side of the Tesla trade and made a lot of money on the stock. In the section below, I will summarize some of the key arguments, with my responses.

- Revenues of "only $400 billion": The most common critique seems to be that I am giving Tesla "only $400 billon in revenues" in 2032, and that this "much too conservative", given its multiple business lines and immense potential. My response to that is that it is only because of Tesla's multiple business lines and immense potential that I am estimating revenues of $400 billion for Tesla, and that number is hard to reach. In fact, in January 2023, there were only five companies in the world that reported annual revenues exceeding $400 billion and they are listed below:Since the $400 billion is in 2032 dollars, I have also reported companies with revenues that exceed $300 billion in 2023 on the table and the list expands, but only to ten firms. There are three lessons that I draw from this table. The first is that while $400 billion in revenues is clearly plausible, it is a difficult target for a firm to hit, and while you can use a higher growth rate than I use, and arrive at end revenues of a $1 trillion or more, you are estimating revenues that no company in history has ever generated. The second is that barring the oil companies, whose revenues and margins ebb and flow with oil prices, the only firm on this list that generates double digit margins is Apple, which has been rewarded with the largest market capitalization of any company in the world. Put simply, there are very, very few companies that generate big revenues and earn high margins at the same time. Third, there are only two companies on this list that have had double digit revenue growth rates in the last decade, Amazon and United Health, and the former generates operating margins in the low single digits. Firms with large revenues find it difficult to maintain high growth, as they scale up.

- Operating margins of only 16%: The second critique of my valuation is that I am using an operating margin of "only 16%", backed by two arguments. The first is that Tesla has a superior product to sell and that its customers are loyal, giving it pricing power, and that should lead to higher margins. The second, and more compelling one, is that Tesla has actually been able to deliver margins that exceed 16%, and that as it scales up, economies of scale will lead to increasing margins. On both fronts, I am more cautious. The operating margins that you can deliver as a company depend on product quality and pricing power, but they are also underpinned by unit economics. The companies that deliver the highest margins incur very low costs in producing the next units that they sell, and that is why software companies, tobacco companies and Aramco have sky-high margins. The bulk of Tesla's revenues, in my view, will come from its auto business (cars, trucks, automated cars...) and the costs of manufacturing an automobile, no matter how efficient you are at operations, are substantial. With legacy auto companies, the median operating margin is about 5-6%, with very few (perhaps a few luxury or niche auto companies) with double-digit margins. It is true that Tesla has businesses, perhaps in energy and software, where it can generate operating margins that are higher, but these businesses, by their very nature, are more likely to deliver billions of dollars in revenues, rather than hundred of billions. On the second point, the notion that economies of scale continue to show up no matter how large a company is a myth; economies of scale are greatest as companies go from small to large, but they level off once you scale up. I believe that Tesla has already harvested the bulk of its economies of scale benefits, and will face a tougher grind going forward , and time will tell whether I am wrong on this front.

- Multiple Businesses: One of the most common critiques from Tesla bulls is that my valuation fails to incorporate all of the businesses that Tesla operates in, and that I was valuing it as an auto company. That is not true! In fact, it is precisely because Tesla has other businesses (software, energy, batteries) that it can use to augment its core auto revenues that I assume that revenues can get to $400 billion, making it larger than any other auto company in the world by a third and that operating margins will stay at 16%, which no auto company can sustain. It is true that I don't break revenues down, by business, but that reflects my view that breaking things into detail, without any real basis for forecasting detailed line items creates the illusion of precision, while actually making your valuation less so. The only business, which if it comes to fruition, that could materially affect the revenues is autonomous driving, and I have to confess that I find that there is more loose talk than analysis on that front. In fact, if the reason that you are buying Tesla is because you believe that they have the lead in this space, you may want to pause and ask what part of autonomous driving will be occupied by the company. The revenue/margin/reinvestment assumptions that you will make will be very different if Tesla just manufactures and sell cars with autonomous driving capacity to others (private car owners, ride sharing companies) in the space than if Tesla owned the cars and operates the autonomous business itself. Having watched ridesharing companies like Uber, Lyft and Didi struggle to make money in that business, I remain skeptical about this space being a gold mine for Tesla.

- Angst about terminal value: As I noted in the last section, the questions around the growth rate I assume in year 10, and the 3.47% growth rate forever have less to do with Tesla and more to do with the economy. Every company, as it scales up, will hit a wall, where it has become so large that it can grow, at best, at the rate that the economy (domestic or global) that the company operates in. For some companies, that wall comes with larger revenues than others, and the very best companies are able to delay hitting the wall for longer. I have assumed that Tesla reaches this status, when it has revenues of $400 billion, and around year 10. You may decide that this is too pessimistic, but if you do so, the response is not to increase the growth rate from 3.47% to a higher value after year 10, but to either use higher growth in the next ten years to reach revenues of $500 or $600 billion in year 10, or lengthen the growth period to 15 or 20 years. If you do the latter, remember that growth dissipates between 4-6 years for most growth companies, ten years is already at the 90th percentile of growth periods for the companies and using 20-25 years of growth risks making your company a unicorn.

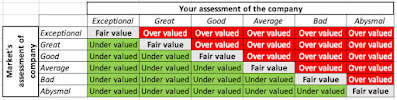

- Exceptional company: I know that none of what I have said so far will be convincing for some of you, who believe that Tesla is not just the next great company, but a one-of-a-kind company, and I accept that. If you believe that, you may very well be okay with letting Tesla's annual revenues hit a trillion and pushing operating margins to 20%. However, exceptional companies may or may not be exceptional or even good investments, if the market prices in their payoff, just as abysmal companies may not bad investments, if the market prices that in. The picture below simplifies the choice:In short, making the argument that Tesla is a very good, great or even exceptional company is only half the investment game, with assessing what the market is pricing in being the other half. It was the reason that I argued at a $1.2 trillion dollar market capitalization, in November 2021, even Tesla exceptionalists should reconsider investing in the company, since paying an upfront price for a company to be exceptional leaves you no upside. At best, the company will deliver on its exceptionalism, and you will make a fair return (essentially equivalent to what you would earn on an index fund), and at worst, the company may turn out to be only great or very good, both of which are now negative surprises. I am valuing Tesla to be an immensely successful company, and at the right price ($12 in 2019, $97 in December 2022), I believe that it is a good, perhaps even a great, investment.

- Premiums for Vision: There is a final critique that I find almost incomprehensible, where Tesla is posited to be so special a company and Musk such an out-of-the-box visionary that you cannot capture its value in earnings and cash flows. That is sophistry, at best, since when you pay a price for Tesla's shares, you are putting a value to these ephemeral qualities, with the only difference being that you implicitly assume that these qualities will justify the price that you are paying and in an intrinsic valuation, you have to explicitly work out how these qualities translate into earnings, growth and risk characteristics.

From Tesla Bears

For the moment, Tesla bears seem to be happier with me than Tesla bulls, though that may change on my next valuation. Their arguments, though, are that I am over estimating value, and their critiques can be summarized below.

- Recession and price cuts: Coming in 2023, Tesla has been cutting the prices of its products, and with economists predicting a recession, my assumptions of 24% growth in revenues and 17.99% margins have been described as "whistling past the grave yard". That is true, but a recession-induced lower revenues growth/margins in the near term will have little or no effect on the valuation, since you will recover on both counts as the economy bounces back. Lowering revenue growth to 15% in 2023 and raising it to 33% in 2024 will deliver almost the same value for the company, as what I get with my smoothed-out values. If you are a long term investor, you are buying a company across economic cycles, not just through the next one, and expectations of a recession may, at best, affect your investment timing more than it does investment value.

- Just a car company: Taking the other side of the Tesla bull argument, Tesla bears view the higher revenues and margins that I am forecasting as coming from Tesla's other businesses as a pipe dream. In their view, Tesla software will be bundled with the automobiles and be incapable of delivering additional revenues or profits on its own and autonomous driving is a space that will take a lot longer to actualize, with Tesla facing competition from Google and other tech giants, not other states quo auto companies. I am truly in the middle on this one, splitting the difference between the hundreds of billions that Tesla bulls see as coming from other businesses and the zeros that the Tesla bears attribute to other businesses.

- Cost of capital: To the argument that 10.15% is too low a cost of capital to use on a company like Tesla, in a cyclical business and with a unpredictable CEO at its helm, my response is the same it was to the Tesla bulls (who wanted me to use a much lower cost of capital). It is that there is not much room for disagreement on this measure, and much as analysts may want to let their senses drive them, and in the current market environment, costs of capital of 15% or 6% are just off the table.

Conclusion

I know that you may not believe me on this claim, but I am in neither the Tesla bull nor the Tesla bear camp. It is true that in my valuations of the company, I have found it to be overvalued more frequently than I have have found it to be under valued. That said, I did buy Tesla in 2019, and while I held the stock for only seven months, before I sold it, I am clearly not in the "I will never buy Tesla" camp. If your counter is that I would have been far richer, if I had just bought Tesla and held, that is true, but I would have to abandon an investment philosophy that has not only worked for me, but also allows me to pass the sleep test.

Finally, while the dissent and disagreement was mostly polite (and I thank you for that!), I am puzzled by some of the vitriol on the part of those who disagree with my Tesla story and valuation. I am not in the business of dishing out investment advice, and the only person that my valuation was meant for, was me, and I aim to act on it. I am not trying to convince you, if you are a Tesla bull, that you are wrong and should sell your stock, or if you are a Tesla bear, that you should buy the stock, if it drops below $130. The very fact that you are letting my valuation, which reflects my view and value, shake your conviction should tell you more about your conviction (or perhaps the lack of it) than about my valuation. So buy Tesla, sell Tesla or sit on the sidelines, but no matter what you do, God speed, and good luck!

YouTube Video

No comments:

Post a Comment