In this post, I will bring together two disparate and very different topics that I have written about in the past. The first is the role that cash holdings play in a business, an extension of the dividend policy question, with an examination of why businesses often should not pay out what they have available to shareholders. In my classes and writing on corporate finance, I look at the motives for businesses retaining cash, as well as how much cash is too much cash. The second is bitcoin, which can be viewed as either a currency or a collectible, and in a series of posts, I argued that bitcoin can only be priced, not valued, making debates about whether to buy or not to buy entirely a function of perception. In fact, I have steered away from saying much about bitcoin in recent years, though I did mention it in my post on alternative investments as a collectible (like gold) that can be added to the choice mix. While there may be little that seemingly connects the two topics (cash and bitcoin), I was drawn to write this post because of a debate that seems to be heating up on whether companies should put some or a large portion of their cash balances into bitcoin, with the success of MicroStrategy, a high-profile beneficiary of this action, driving some of this push. I believe that it is a terrible idea for most companies, and before Bitcoin believers get riled up, my reasoning has absolutely nothing to do with what I think of bitcoin as an investment and more to do with how little I trust corporate managers to time trades right. That said, I do see a small subset of companies, where the holding bitcoin strategy makes sense, as long as there are guardrails on disclosure and governance.

Cash in a Going Concern

In a world where businesses can raise capital (equity or debt) at fair prices and in a timely manner, there is little need to hold cash, but that is not the world we live in. For a variety of reasons, some internal and some external, companies are often unable or unwilling to raise capital from markets, and with that constraint in place, it is logical to hold cash to meet unforeseen needs. In this section, I will start by laying out the role that cash holdings play in any business, and examine how much cash is held by companies, broken down by groupings (regional, size, industry).

A Financial Balance Sheet

To understand the place of cash in a business, I will start with a financial balance sheet, a structure for breaking down a business, public or private:

On the asset side of the balance sheet, you start with the operating business or businesses that a company is in, with a bifurcation of value into value from investments already made (assets-in-place) and value from investments that the company expects to make in the future (growth assets). The second asset grouping, non-operating assets, includes a range of investments that a company may make, sometimes to augment its core businesses (strategic investments), and sometimes as side investments, and thus include minority holdings in other companies (cross holdings) and even investments in financial assets. Sometimes, as is the case with family group companies, these cross holdings may be a reflection of the company's history as part of the group, with investments in other group companies for either capital or corporate control reasons. The third grouping is for cash and marketable securities, and this is meant specifically for investments that share two common characteristics - they are riskless or close to riskless insofar as holding their value over time and they are liquid in the sense that they can be converted to cash quickly and with no penalty. For most companies, this has meant investing cash in short-term bonds or bills, issued by either governments (assuming that they have little default risk) or by large, safe companies (in the form of commercial paper issued by highly rated firms).

Note that there are two sources of capital for any business, debt or equity, and in assessing how levered a firm is, investors look at the proportion of the capital that comes from each:

- Debt to Equity = Debt/ Equity

- Debt to Capital = Debt/ (Debt + Equity)

In fact, there are many analysts and investors who estimate these debt ratios, using net debt, where they net the cash holdings of a company against the debt, with the rationale, merited or not, that cash can be used to pay down debt.

- Net Debt to Equity = (Debt-Cash)/ Equity

- Debt to Capital = (Debt-Cash)/ (Debt + Equity)

The Motives for holding Cash

In my introductory finance classes, there was little discussion of cash holdings in companies, outside of the sessions on working capital. In those sessions, cash was introduced as a lubricant for businesses, necessary for day-to-day operations. Thus, a retail store that had scores of cash customers, it was argued, needed to hold more cash, often in the form of currency, to meet its transactional needs, than a company with corporate suppliers and business customers, with predictable patterns in operations. In fact, there were rules of thumb that were developed on how much cash a company needed to have for its operations. As the world shifts away from cash to digital and online payments, this need for cash has decreased, but clearly not disappeared. The one carve out is the financial services sector, where the nature of the business (banking, trading, brokerage) requires companies in the sector to hold cash and marketable securities as part of their operating businesses.

If the only reason for holding cash was to cover operating needs, there would be no way to justify the tens of billions of dollars that many companies hold; Apple alone has often had cash balances that exceeded $200 billion, and the other tech giants are not far behind. For some companies, at least, the rationale for holding far more cash than justified by their operating needs is that it can operate as a shock absorber, something that they can fall back on during periods of crisis or to cover unexpected expenses. That is the reason that cyclical and commodity firms have often offered for holding large cash balances (as a percent of their overall firm value), since a recession or a commodity price downturn can quickly turn profits to losses.

Using the corporate life cycle structure can also provide insight into how the motives for holding cash can change as a company ages.

For start-ups, that are either pre-revenue or have very low revenues, cash is needed to keep the business operating, since employees have to be paid and expenses covered. Young firms that are money-losing and with large negative cash flows, hold cash to cover future cash flow needs and to fend off the risk of failure. In effect, these firms are using cash as life preservers, where they can make it through periods where external capital (venture capital, in particular) dries up, without having to sell their growth potential at bargain basement prices. As firms start to make money, and enter high growth, cash has use as a business scalar, for firms that want to scale up quickly. In mature growth, cash acquires optionality, useful in allowing the business to find new markets for its products or product extensions. Mature firms sometimes hold cash as youth serum, hoping that it can be used to make once-in-a-lifetime investments that may take them back to their growth days, and for declining firms, cash becomes a liquidation manager, allowing for the orderly repayment of debt and sale of assets.

There is a final rationale for holding cash that is rooted in corporate governance and the control and power that comes from holding cash. I have long argued that absent pressure from shareholders, managers at most publicly traded firms would choose to return very little of the cash that they generate, since that cash balance not only makes them more sought after (by bankers and consultants who are endlessly inventive about uses that the cash can be put to) but also gives them the power to build corporate empires and create personal legacies.

Corporate Cash Holdings

Given the multitude of reasons for holding cash, it should come as no surprise that publicly traded companies around the world have significant cash balances. Leading into July 2025, for instance, global non-financial-service firms held almost $11.4 trillion in cash and marketable securities; financial service firms held even more in cash and marketable securities, but those holdings, as we noted earlier, can represent their business needs. Using our earlier breakdown of the asset side of the balance sheet into cash, non-operating and operating assets, this is what non-financial service firms in the aggregate looked like in book value terms (global and just US firms):

The typical publicly traded firm holds a large cash balance, but there are significant differences in cash holdings, by sector. In the table below, I look at cash as a percent of total assets, a book value measure, as well as cash as a percent of firm value, computed by aggregating market values:

As you can see, technology firms, which presumably face more uncertainty about their future hold far more cash as a percent of book value, but the value that the market attaches to their growth brings down cash as a percent of firm value. Utilities, regulated and often stable businesses, tend to hold the least cash, both in book and market terms.

Breaking down the sample by region, I look at cash holdings, as a percent of total assets and firms, across the globe:

The differences across the globe can be explained by a mix of market access, with countries in parts of the world where it can be difficult to access capital (Latin America, Eastern Europe, Africa) holding more cash. In addition, and corporate governance, with cash holdings being greater in parts of the world (China, Russia) where shareholders have less power over managers.

Given the earlier discussion of how the motives for holding cash can vary across the life cycle, I broke the sample down by age decile, with age measured from the year of founding, and looked at cash holdings, by decile:

The results are mixed, with cash holdings as a percent of total assets being higher for the younger half of the sample (the top five deciles) than for the older half, but the is no discernible pattern, when cash is measured as a percent of firm value (market). Put simple, companies across the life cycle hold cash, though with different motives, with the youngest firms holding on to cash as lifesavers (and for survival) and the older firms keeping cash in the hopes that they can use it to rediscover their youth.

The Magic of Bitcoin

I have been teaching and working with investments now for four decades, and there has been no investment that has received as much attention from both investors and the financial press, relative to its actual value, as has bitcoin. Some of the draw has come from its connections to the digital age, but much of it has come from its rapid rise in price that has made many rich, with intermittent collapses that have made just as many poor. I am a novice when it comes to crypto, and while I have been open about the fact that it is not my investment preference, I understand its draw, especially for younger investors.

The Short, Eventful History of Bitcoin

The origin story for Bitcoin matters since it helps us understand both its appeal and its structure. It was born in November 2008, two months into one of the worst financial crises of the last century, with banks and governments viewed as largely responsible for the mess. Not surprisingly, Bitcoin was built on the presumption that you cannot trust these institutions, and its biggest innovation was the blockchain, designed as a way of crowd-checking transactions and preserving transaction integrity. I have long described Bitcoin as a currency designed by the paranoid for the paranoid, and I have never meant that as a critique, since in the untrustworthy world that we live in, paranoia is a justifiable posture.

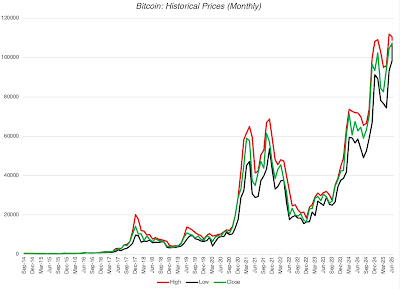

From its humble beginnings, where only a few (mostly tech geeks) were aware of its existence, Bitcoin has accumulated evangelists, who argue that it is the currency of the future, and speculators who have used its wild price swings to make and lose tens of millions of dollars. In the chart below, I look at the price of bitcoin over the last decade, as its price has increased from less than $400 in September 2014 to more than $110,000 in June 2025:

Along the way, Bitcoin has also found some acceptance as a currency, first for illegal activities (drugs on the Silk Road) and then as the currency for countries with failed fiat currencies (like El Salvador), but even Bitcoin advocates will agree that its use in transactions (as the medium of exchange) has not kept pace with its growth as a speculative trade.Pricing Bitcoin

In a post in 2017, I divided investments into four groups - assets that generate cash flows (stocks, bonds, private businesses), commodities that can be used to produce other goods (oil, iron ore etc), currencies that act as mediums of exchange and stores of value and collectibles that are priced based on demand and supply:

The MicroStrategy Story

It is undeniable that one company, MicroStrategy, has done more to advance the corporate holding of Bitcoin than any other, and that has come from four factors;

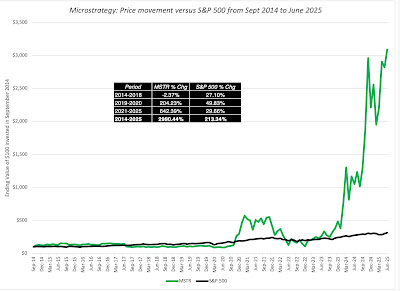

- A stock market winner: The company's stock price has surged over the last decade, making it one of the best performing stocks on the US exchanges: It is worth noting that almost all of the outperformance has occurred in this decade, with the winnings concentrated into the last two years.

- With the rise (increasingly) tied to Bitcoin: Almost all of MicroStrategy’s outperformance has come from its holdings of bitcoin, and not come from improvements in business operations. That comes through in the graph below, where I look at the prices of MicroStrategy and Bitcoin since 2014:

Note that MicroStrategy’s stock price has gone from being slightly negatively correlated with Bitcoin’s price between 2014-2018 to tracking Bitcoin in more recent years. - And disconnected from operations: In 2014, MicroStrategy was viewed and priced as a software/services tech company, albeit a small one with promise. In the last decade, its operating numbers have stagnated, with both revenues and gross profits declining, but during the same period, its enterprise value has soared from $1 billion in 2014 to more than more than $100 billion in July 2025:

It is clear now that anyone investing in MicroStrategy at its current market cap (>$100 billion) is making a bitcoin play. - With a high-profile "bitcoin evangelist" as CEO: MicroStrategy’s CEO, Michael Saylor, has been a vocal and highly visible promoter of bitcoin, and has converted many of his shareholders into fellow-evangelists and convinced at least some of them that he is prescient in detecting price movements. In recent years, he has been public in his plans to issue increasing amounts of stock and using the proceeds to buy more bitcoin.

The “Put your cash in bitcoin” movement

For investors in other publicly traded companies that have struggled delivering value in their operating businesses, MicroStrategy’s success with its bitcoin holdings seems to indicate a lost opportunity, and one that can be remedied by jumping on the bandwagon now. In recent months, even high profile companies, like Microsoft, have seen shareholder proposals pushing them to abandon their conventional practice of holding cash in liquid and close-to-riskless investments and buying Bitcoin instead. Microsoft’s shareholders soundly rejected the proposal, and I will start by arguing that they were right, and that for most companies, investing cash in bitcoin does not make sense, but in the second part, I will carve out the exceptions to this rule.

The General Principle: No to Bitcoin

As a general rule, I think it is not only a bad idea for most companies to invest their cash in bitcoin, but I would go further and also argue that they should banned from doing so. Let me hasten to add that I would make this assertion even if I was bullish on Bitcoin, and my argument would apply just as strongly to companies considering moving their cash into gold, Picassos or sports franchises, for five reasons:

- Bitcoin does not meet the cash motives: Earlier in this post, I noted the reasons why a company holds cash, and, in particular, as a shock absorber, steadying a firm through bad times. Replacing low-volatility cash with high-volatility bitcoin would undercut this objective, analogous to replacing your shock absorbers with pogo sticks. In fact, given the history of moving with stock prices, the value of bitcoin on a company's balance sheet will dip at exactly the times where you would need it most for stability. The argument that bitcoin would have made a lot higher returns for companies than holding cash is a non-starter, since companies should hold cash for safety.

- Bitcoin can step on your operating business narrative: I have long argued that successful businesses are built around narratives that incorporate their competitive advantages. When companies that are in good businesses put their cash in bitcoin, they risk muddying the waters on two fronts. First, it creates confusion about why a company with a solid business narrative from which it can derive value would seek to make money on a side game. Second, the ebbs and flows of bitcoin can affect financial statements, making it more difficult to connect operating results to story lines.

- Managers as traders? When companies are given the license to move their cash into bitcoin or other non-operating investments, you are trusting managers to get the timing right, in terms of when to buy and sell these investments. That trust is misplaced, since top managers (CEOs and CFOs) are for the most part terrible traders, often buying at the market highs and selling at lows.

- Leave it to shareholders: Even if you are unconvinced by the first three reasons, and you are a bitcoin advocate or enthusiast, you will be better served pushing companies that you are a shareholder in, to return their cash to you, to invest in bitcoin, gold or any other investment at your chosen time. Put simply, if you believe that Bitcoin is the place to put your money, why would you trust corporate managers to do it for you?

- License for abuse: I am a skeptic when it comes to corporate governance, believing that managerial interests are often at odds with what's good for shareholders. Giving managers the permission to trade crypto tokens, bitcoin or other collectibles can open the door for self dealing and worse.

The Carveouts

I do believe that there are cases when you, as a shareholder, may be at peace with the company not only investing cash in bitcoin, but doing so actively and aggressively. Here are four of my carveouts to the general rule on bitcoin:

- The Bitcoin Savant: In my earlier description of MicroStrategy, I argued that shareholders in MicroStrategy have not only gained immensely from its bitcoin holdings, but also trust Michael Saylor to trade bitcoin for them. In short, the perception, rightly or wrongly, is that Saylor is a bitcoin savant, understanding the mood and momentum swings better than the rest of us. Generalizing, if a company has a leader (usually a CEO or CFO) who is viewed as someone who is good at gauging bitcoin price direction, it is possible that shareholders in the company may be willing to grant him or her the license to trade bitcoin on their behalf. This is, of course, not unique to bitcoin, and you can argue that investors in Berkshire Hathaway have paid a premium for its stock, and allowed it leeway to hold and deploy immense amounts of cash because they trusted Warren Buffett to make the right investment judgments.

- The Bitcoin Business: For some companies, holding bitcoin may be part and parcel of their business operations, less a substitute for cash and more akin to inventory. PayPal and Coinbase, both of which hold large amounts of bitcoin, would fall into this carveout, since both companies have business that requires that holding.

- The Bitcoin Escape Artist: As some of you may be aware, I noted that Mercado Libre, a Latin American online retail firm, is on my buy list, and it is a company with a fairly substantial bitcoin holding. While part of that holding may relate to the operating needs of their fintech business, it is worth noting that Mercado Libre is an Argentine company, and the Argentine peso has been a perilous currency to hold on to, making bitcoin a viable option for cash holdings. Generalizing, companies in countries with failed currencies may conclude that holding their cash in bitcoin is less risky than holding it in the fiat currencies of the locations they operate in.

- The Bitcoin Meme: There is a final grouping of companies that I would put in the meme stock category, with AMC and Gamestop heading that list. These companies have operating business models that have broken down or have declining value, but they have become, by design or through accident, trading plays, where the price bears no resemblance to operating fundamentals and is instead driven by mood and momentum. If that is the case, it may make sense for these companies to throw in the towel on operating businesses entirely and instead make themselves even more into trading vehicles by moving into bitcoin, with the increased volatility adding to their "meme" allure.

Even with these exceptions, though, I think that you need guardrails before signing off on opening the door to letting companies hold bitcoin.

- Shareholder buy-in: If you are a publicly traded company considering investing some or much of the company's cash in bitcoin, it behooves you to get shareholder approval for that move, since it is shareholder cash that is being deployed.

- Transparency about Bitcoin transactions/holdings: Once a company invests in bitcoin, it is imperative that there be full and clear disclosure not only on those holdings but also on trading (buying and selling) that occurs. After all, if it is a company's claim that it can time its bitcoin trades better than the average investor, it should reveal the prices at which it bought and sold its bitcoin.

- Clear mark-to-market rules: If a company invests its cash in bitcoin, I will assume that the value of that bitcoin will be volatile, and accounting rules have to clearly specify how that bitcoin gets marked to market, and where the profits and losses from that marking to market will show up in the financial statements.

Cui Bono?

Bitcoin advocates have been aggressively pushing both institutional investors and companies to include Bitcoin in their investment choices, and it is true that at least first sight, they will benefit from that inclusion. Expanding the demand for bitcoin, an investment with a fixed supply, will drive the price upwards, and existing bitcoin holders will benefit. In fact, much of the rise of bitcoin since the Trump election in November 2024 can be attributed to the perception that this administration will ease the way for companies and investors to join in the crypto bonanza.

For bitcoin holders, increasing institutional and corporate buy-in to bitcoin may seem like an unmixed blessing, but there will be costs that, in the long run, may lead at least some of them to regret this push:

- Different investor base: Drawing in institutional investors and companies into the bitcoin market will not only change its characteristics, but put traders who may know how to play the market now at a disadvantage, as it shifts dynamics.

- Here today, gone tomorrow? Bitcoin may be in vogue now, but what will the consequences be if it halves in price over the next six months? Institutions and companies are notoriously ”sheep like” in their behavior, and what is in vogue today may be abandoned tomorrow. If you believe that bitcoin is volatile now, adding these investors to the mix will put that volatility on steroids.

- Change asset characteristics: Every investment class that has been securitized and brought into institutional investing has started behaving like a financial asset, moving more with stocks and bonds than it has historically. This happened with real estate in the 1980s and 1990s, with mortgage backed securities and other tradable versions of real estate, making it far more correlated with stock and bonds, and less of a stand alone asset.