In every introductory finance class, you begin with the notion of a risk-free investment, and the rate on that investment becomes the base on which you build, to get to expected returns on risky assets and investments. In fact, the standard practice that most analysts and investors follow to estimate the risk free rate is to use the government bond rate, with the only variants being whether they use a short term or a long term rate. I took this estimation process for granted until 2008, when during that crisis, I woke up to the realization that no matter what the text books say about risk-free investments, there are times when finding an investment with a guaranteed return can become an impossible task. In the aftermath of that crisis, I wrote a series of what I called my nightmare papers, starting with one titled, "What if nothing is risk free?", where I looked at the possibility that we live in a world where nothing is truly risk free. I was reminded of that paper a few weeks ago, when Fitch downgraded the US, from AAA to AA+, a relatively minor shift, but one with significant psychological consequences for investors in the largest economy in the world, whose currency still dominates global transactions. After the rating downgrade, my mailbox was inundated with questions of what this action meant for investing, in general, and for corporate finance and valuation practice, in particular, and this post is my attempt to answer them all with one post.

Risk Free Investments: Definition, Role and Measures

The place to start a discussion of risk-free rates is by answering the question of what you need for an investment to be risk-free, following up by seeing why that risk-free rate plays a central role in corporate finance and investing and then looking at the determinants of that risk-free rate.

What is a risk free investment?

For an investment to be risk-free, you have feel certain about the return you will make on it. With this definition in place, you can already see that to estimate a risk free rate, you need to be specific about your time horizon, as an investor.

- An investment that is risk free over a six month time period will not be risk free, if you have a ten year time horizon. That is because you have reinvestment risk, i.e., the proceeds from the six-month investment will have to be reinvested back at the prevailing interest rate six months from now, a year from now and so on, until year 10, and those rates are not known at the time you take the first investment.

- By the same token, an investment that delivers a guaranteed return over ten years will not be risk free to an investor with a six month time horizon. With this investment, you face price risk, since even though you know what you will receive as a coupon or cash flow in future periods, since the present value of these cash flows, will change as rates change. During 2022, the US treasury did not default, but an investor in a 10-year US treasury bond would have earned a return of -18% on his or her investment, as bond prices dropped.

For an investment to be risk free then, it has to meet two conditions. The first is that there is no risk that the issuer of the security will default on their contractual commitments. The second is that the investment generates a cash flow only at your specified duration, and with no intermediate cash flows prior to that duration, since those cash flows will then have to be reinvested at future, uncertain rates. For a five-year time horizon, then, you would need the rate on a five-year zero default-free zero coupons bond as your risk-free rate.

You can also draw a contrast between a nominal risk-free rate, where you are guaranteed a return in nominal terms, but with inflation being uncertain, the returns you are left with after inflation are no longer guaranteed, and a real risk-free rate, where you are guaranteed a return in real terms, with the investment is designed to protect you against volatile inflation. While there is an appeal to using real risk-free rates and returns, we live in a world of nominal returns, making nominal risk-free rates the dominant choice, in most investment analysis.

Why does the risk-free rate matter?

By itself, a risk-free investment may seem unexceptional, and perhaps even boring, but it is a central component of investing and corporate finance:

- Asset Allocation: Investors vary on risk aversion, with some more willing to take risk than others. While there are numerous mechanisms that they use to reflect their differences on risk tolerance, the simplest and the most powerful is in their choice on how much to invest in risky assets (stocks, corporate bonds, collectibles etc.) and how much to hold in investments with guaranteed returns over their time horizon (cash, treasury bill and treasury bonds).

- Expected returns for Risky Investments: The risk-free rate becomes the base on which you build to estimate expected returns on all other investments. For instance, if you read my last post on equity risk premiums, I described the equity risk premium as the additional return you would demand, over and above the risk free rate. As the risk-free rate rises, expected returns on equities will be pushed up, and holding all else constant, stock prices will go down., and the reverse will occur, when risk-free rates drop.

- Hurdle rates for companies: Using the same reasoning, higher risk-free rates push up the costs of equity and debt for all companies, and by doing so, raise the hurdle rates for new investments. As you increase hurdle rates, new investments will have to earn higher returns to be acceptable, and existing investments can cross from being value-creating (earning more than the hurdle rate) to value-destroying (earning less).

- Arbitrage pricing: Arbitrage refers to the possibility that you can create risk-free positions by combining holdings in different securities, and the benchmark used to judge whether these positions are value-creating becomes the risk-free rate. If you do assume that markets will price away this excess profit, you then have the basis for the models that are used to value options and other derivative assets. That is why the risk-free rate becomes an input into option pricing and forward pricing models, and its absence leaves a vacuum.

Determinants

So, why do risk-free rates vary across time and across currencies? If your answer is the Fed or central banks, you have lost the script, since the rates that central banks set tend to be short-term, and inaccessible, for most investors. In the US, the Fed sets the Fed Funds rate, an overnight intra-bank borrowing rate, but US treasury rates, from the 3-month to 30-year, are set at auctions, and by demand and supply. To understand the fundamentals that determine these rates, put yourself in the shoes of a buyer of these securities, and consider the following:

- Inflation: If you expect inflation to be 3% in the next year, it makes little sense to buy a bond, even if it is default free, that offers only 2%. As expected inflation rises, you should expect risk-free rates to rise, with or without central bank actions.

- Real Interest Rate: When you buy a note or a bond, you are giving up current consumption for future consumption, and it is fitting that you earn a return for this sacrifice. This is a real risk-free rate, and in the aggregate, it will be determined by the supply of savings in an economy and the demand for those savings from businesses and individuals making real investments. Put simply, economies with a surplus of growth investments, i.e., with more real growth, should see higher real interest rates, in steady state, than stagnant or declining economies.

The recognition of these fundamentals is what gives rise to the Fisher equation for interest rates or the risk free rate:

Nominal Risk-free Rate = (1 + Expected Inflation) (1+ Real Interest Rate) -1 (or)

= Expected Inflation + Expected Real Interest Rate (as an approximation)

If you are wondering where central banks enter this equation, they can do so in three ways. The first is that central banking actions can affect expected inflation, at least in the long term, with more money-printing leading to higher inflation. The second is central banking actions can, at least at the margin, push rates above their fundamentals (expected inflation and real interest rates), by tightening monetary policy, and below their fundamentals by easing monetary policy. Since this is often achieved by raising or lowering the very short term rates set by the central bank, the central banking effect is likely to be greater at the shorter duration risk-free rates. The third is that central banks, by tightening or easing monetary policy, may affect real growth in the near term, and by doing so, affect real rates.

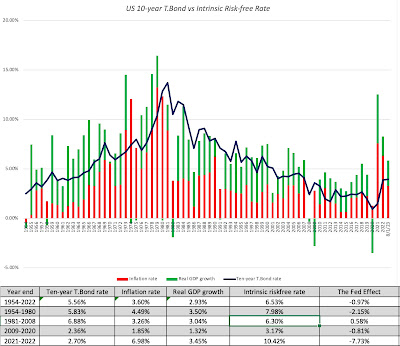

Having been fed the mythology that the Fed (or another central bank) set interest rates by investors and the media, you may be unconvinced, but there is no better way to show the emptiness of "the Fed did it" argument than to plot out the US treasury bond rate each year against a crude version of the fundamental risk-free rate, computed by adding the actual inflation in a year to the real GDP growth rate that year:

As you can see, the primary reasons why we saw historically low rates in the 2008-2021 time period was a combination of very low inflation and anemic real growth, and the main reason that we have seen rates rise in 2022 and 2023 is rising inflation. It is true that nominal rates follow a smoother path than the intrinsic risk free rates, but that is to be expected since the ten-year rates represent expected values for inflation and real growth over the next decade, whereas my estimates of the intrinsic rates represent one-year numbers. Thus, while inflation jumped in 2021 and 2022 to 6.98%, and investors are expecting higher inflation in the future, they are not expecting inflation to stay at those levels for the next decade.

Risk Free Rate: Measurement

Now that we have established what a risk-free rate is, why it matters and its determinants, let us look at how best to measure that risk-free rate. We will begin by looking at the standard practice of using government bond rates as riskfree rates, and why it collides with reality, move on to examine why governments default and end with an assessment of how to adjust government bond rates for that default risk.

Government Bond Rates as Risk Free

I took my first finance class a long, long time ago, and during the risk-free rate discussion, which lasted all of 90 seconds, I was told to use the US treasury rate as a risk-free rate. Not only was this an indication of how dollar-centric much of finance education used to be, but also of how much faith there was that the US treasury was default-free. Since then, as finance has globalized, that lesson has been carried, almost unchanged, into other currencies, where we are now being taught to use government bond rates in those currencies as risk-free rates. While that is convenient, it is worth emphasizing two implicit assumptions that underlie why government bond rates are viewed as risk-free:

- Control of the printing presses: If you have heard the rationale for government bond rates as risk-free rates, here is how it usually goes. A government, when it borrows or issues bonds in its local currency, preserves the option to print more money, when that debt comes due, and thus should never default. This assumption breaks down, of course, when countries share a common currency, as is the case with the dozen or more European countries that all use the Euro as their domestic currency, and none of them has the power to print currency at will.

- Trust in government: Governments that default, especially on their domestic currency borrowings, are sending a signal that they cannot be trusted on their obligations, and the implicit assumption is that no government that has a choice would ever send that signal. (Governments send the same signal when they default on their foreign currency debt/bonds, but they can at least point to circumstances out of their control for doing so.)

When and Why Governments Default

Now that we have established that governments can default, let’s look at why they default. The most obvious reason is economic, where a crisis and collapse in government revenues, from taxes and other sources, causes a government to be unable meet its obligations. The likelihood of this happening should be affected by the following factors:

- Concentrated versus Diversified Economy: A government's capacity to cover its debt obligations is a function of the revenues it generates, and those revenues are likely to be more volatile in a country that gets its revenues from a single industry or commodity than it is in a country with a more diverse economy. One measure of economic concentration is the percent of GDP that comes from commodity exports, and the picture below provides that statistic, by country:

Source: UNCTAD As you can see, much of Africa, Latin America, the Middle East and Asia are commodity dependent, effectively making them more exposed to default, with a downturn in commodity prices. - Degree of Indebtedness: As with companies, countries that borrow too much are more exposed to default risk than countries that borrow less. That said, the question of what to scale borrowing to is an open question. One widely-used measure of country indebtedness is the total debt owed by the country, as a percent of its GDP. Based on that statistic, the most indebted countries are listed below:As you can see, this table contains a mix of countries, with some (Venezuela, Greece and El Salvador) at high risk of default and others (Japan, US, UK, Canada and France) viewed as being at low risk of default.

- Tax Efficiency: It is worth remembering that governments do not cover debt obligations with gross domestic product or country wealth, but with their revenues, which come primarily from collecting taxes. Holding all else constant, governments with more efficient tax systems, where most taxpayers comply and pay their share, are less likely to default than governments with more porous tax systems, where tax evasion is more the rule than the exception, and corruption puts revenues into the hands of private players rather than the government.

There is a second force at play, in sovereign defaults. Ultimately, a government that chooses to default is making a political choice, as much as it is an economic one. When politics is functional, and parties across the spectrum share in the belief that default should be a last resort, with significant economic costs, there will be shared incentive in avoiding default. However, when politics becomes dysfunctional, and default is perceived as partisan, with one side of the political divide perceived as losing more from default than the other, governments may default even though they have the resources to cover their obligations.

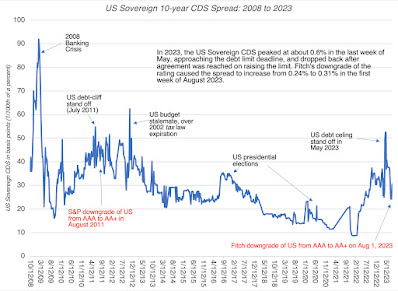

As a lender to a government, you may not care about why a government defaults, but economic defaults generally represent more intractable problems than defaults caused by political dysfunction, which tend to be solved once the partisan pounds of flesh are extracted. In my view, the ratings downgrades of the US government fall into the latter category, since they are triggered by a uniquely US phenomenon, which is a debt limit that has to be reset each time the total debt of the US approaches that value. Since that reset has to be approved by the legislature, it becomes a mechanism for political standoffs, especially when there is a split in executive and legislative power. In fact, the first downgrade of the US occurred more than a decade ago, when S&P lowered its sovereign rating for the US from AAA to AA+ in 2011, after a debt-limit standoff at the time. The Fitch downgrade of the US, this year, was triggered by a stand-off between the administration and Congress a few months ago on the debt-limit, and one that may be revisited in a few weeks again.

Measuring Government Default Risk

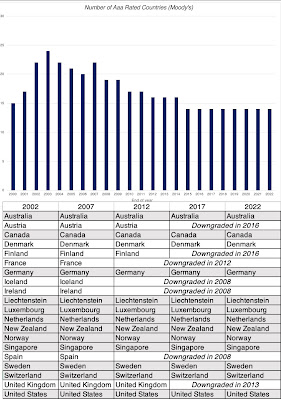

With that lead-in on sovereign default risk, let us look at how sovereign default risk gets measured, again with the US as the focus. The first and most widely used measure of default risk is sovereign ratings, where ratings agencies rate countries, just as they do companies, with a rating scale that goes from AAA (Aaa) down to D(default). Fitch, Moody's and S&P all provide sovereign ratings for countries, with separate ratings for foreign currency and local currency debt. With sovereign ratings, the implicit assumption is that AAA (Aaa) rated countries have negligible or no default risk, and the ratings agencies back this up with the statistic that no AAA rated country has ever defaulted on its debt within 15 years of getting a AAA rating. That said, the number of AAA (Aaa) rated countries has dropped over time, and there are only nine countries left that have the top rating from all three ratings agencies: Germany, Denmark, Netherlands, Sweden, Norway, Switzerland, Luxembourg, Singapore and Australia. Canada is rated AAA by two of the ratings agencies, and after the Fitch downgrade, the US is rated Aaa only by Moody's, whereas the UK is AAA rated only by S&P.

In a reflection of the times, there have been two developments. The first is that the number of countries with the highest rating has dropped over time, as can be seen in the graph below of countries with Aaa ratings from Moody's:

If you recognize that default risk falls on a continuum, rather than in the discrete classes that ratings assign, the sovereign CDS market gives you not only more nuanced estimates of default risk, but ones that are reflect, on an updated basis, what investors think about a country's default risk. The graph below contains the sovereign CDS spreads for the US going back to 2008, and reflect the market's reactions to events (including the 2011 and 2023 debt-limit standoffs) over time:

Dealing with Government Default Risk

No matter what you think about the Fitch downgrade of US government debt, the big-picture perspective is that we are closer to the scenario where no entity is viewed as default-free than we were fifteen years ago, and it may be only a matter of time before we have to retire the notion that government bonds are default-free entirely. The questions for investors and analysts, if this occurs, becomes practical ones, including how best to estimate risk-free rates in currencies, when governments have default risk, and what the consequences are for equity risk premiums and default spreads.

1. Clean up government bond rate

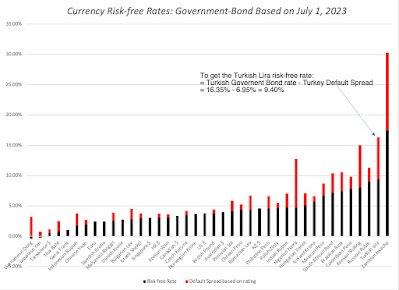

Consider the two requirements that have to be met for a local-currency government bond rate to be used as a risk-free rate in that currency. The first is that the government bond has to be widely traded, making the interest rate on the bond a rate set by demand and supply in the market, rather than government edict. The second is that the government be perceived as default-free. The Swiss 10-year government bond rate, in July 2023, of 1.02% meets both criteria, making it the risk-free rate in Swiss Francs. Using a similar rationale, the German 10-year bund rate (in Euros) of 2.47% becomes the risk-free rate in Euros. With the British pound, if you stay with the Moody's ratings, things get trickier. The government bond rate of 4.42% is no longer risk-free, because it has default risk embedded in it. To clean up that default risk, we estimated a default spread of 0.64%, based upon UK's rating of Aa3, and netted this spread out from the government bond rate:

Risk-free Rate in British Pounds

= Government Bond Rate in Pounds - Default Spread for UK = 4.42% - 0.64% = 3.78%

Extending this approach to all currencies, where there is a government bond rate present, we get the riskfree rates in about 30 currencies:

Riskfree Rate in US dollars = US Treasury Bond Rate - Default spread on US T.Bond

2. Risk Premia

If you focus just on risk-free rates, you may find it counter intuitive that an increase in default risk for a country lowers the risk free rate in its currency, but looking at the big picture should explain why it is necessary. An increase in sovereign default risk is usually triggered by events that also increase risk premia in markets, pushing up government bond rates, equity risk premiums and default spreads. In fact, if you go back to my post on country risk, it becomes the key driver of the additional risk premiums that you demand in countries:

You will notice that in my July 2023 update, I used the implied equity risk premium for the US of 5.00% as my estimate of a premium for a mature market, and assumed that any country with a Aaa rating (from Moody's) would have the same premium.

Since Moody's remains the lone holdout on downgrading the US, I would use the same approach today, but assuming that Moody's downgrades the US from Aaa to Aa1, the approach will have to be modified. The implied equity risk premium for the US will still be my starting point, but countries with Aaa ratings will then be assigned equity risk premiums lower than the US, and that lower equity risk premium will become the mature market premium, to be used to get equity risk premiums for the rest of the world. Using the sovereign CDS spread of 0.30% as the basis, just for illustration, the mature market premium would drop from 5.00%, in my July 2023 update, to 4.58% (5.00% -1.42*.30%).

When safe havens become scarce...

During crises, investors seeks out safety, but that pre-supposes that there is a safe place to put your money, where you know what you will make with certainty. The Fitch downgrade of the US, by itself, is not a market-shaking event, but in conjunction with a minus 18% return on the ten-year US treasury bond in 2022, these events undercut the notion that there is a safe haven for investors. When there is no safe haven, market corrections when they happen will not follow predictable patterns. Historically, when stock prices have plunged, investors have sought out US treasuries, pushing down yields and prices. But what if government securities are viewed as risky? Is it any surprise that the loss of trust in governments that has undercut the perception that they are default-free has also given rise to a host of other investment options, each claiming to be the next safe haven. While my skepticism about crypto currencies and NFTs is well documented, a portion of their rise over the last 15 years has been driven by the erosion of trust in institutions.

Conclusion

I started this post by noting that we pay little attention to risk-free rates in theory and in practice, taking it as a given that it is easy to estimate. As you can see from this post, that casual acceptance of what comprises a risk-free investment can be a recipe for disaster. In closing, here are a few general propositions about risk-free rates that are worth keeping in mind:

- Risk-free rates go with currencies, not countries or governments: You estimate a risk-free rate in Euros or dollars, not one for the Euro-zone or the United States. Thus, if you choose to analyze a Brazilian company in US dollars, the risk-free rate you should use is the US dollar risk free rate, not the rate on Brazilian US-dollar denominated bond. It follows, therefore, that the notion of a global risk-free rate, touted by some, is fantasy, and using the lowest government bond rate, ignoring currencies, as an estimate of this rate, is nonsensical.

- Investment returns should be currency-explicit and time-specific: Would you be okay with a 12% return on a stock, in the long term? That question is unanswerable, until you specify the currency in which you are denominating returns, and the time you are making the assessment. An investment that earns 12%, in Zambian Kwacha, may be making less than the risk-free rate in Kwachas, but one that earns that same return in Swiss Francs should be a slam-dunk as an investment. In the same vein, an investment that earns 12% in US dollars in 2023 may well pass muster as a good investment, but an investment that earned 12% in US dollars in 1980 would not (since the US treasury bond rate would have yielded more than 10% at the time).

- Currencies are measurement mechanisms, not value-enhancer or destroyers: A good financial analysis or valuation should be currency-invariant, with whatever conclusion you draw when you do your analysis in one currency carrying over into the same analysis, done in different currencies. Thus, switching from a currency with a high risk-free rate to one with a much lower risk-free rate will lower your discount rate, but the inflation differential that causes this to happen will also lower your cash flows by a proportional amount, leaving your value unchanged.

- No one (including central banks) cannot fight fundamentals: Central banks and governments that think that they have the power to raise or lower interest rates by edict, and the investors who invest on that basis, are being delusional. While they can nudge rates at the margin, they cannot fight fundamentals (inflation and real growth), and when they do, the fundamentals will win.

YouTube Video