A week ago, I began my series of posts on the drug business, starting with my perspective on how the business is changing and then moving on to posts on Valeant's business model and the runaway story of Theranos. I am finishing this series with a post on Pfizer's plan to merge with Allergan and the economics of the merger. This deal, which will make one of the largest pharmaceutical companies in the world even larger has drawn attention not just because of its magnitude, but also for its motives. While there is some desultory chatter about synergy (as is the case with every merger), this deal seems focused on two specific motivations: the first is that this is a bid by Pfizer to buy Allergan's higher growth and the second is that this is a deal designed to save taxes. Not surprisingly, the latter is attracting attention not just from investors and financial journalists, but also from politicians.

Growth but at what cost?

One of the most dangerous maxims in both corporate finance and investing is that it is better to grow than to not grow, and that a company that faces stagnant or declining revenues (and income) should seek out higher growth (at any price). In a post from a long time ago, I looked at the value of growth and noted that the net effect of growth depends on how much you pay to get it, and that overpaying for growth will give you higher growth and a lower value. In the graph below, you can see the effect of growth on value for three companies, all of which grow, the first by making investments that generate returns that exceed the cost of capital, the second by making investments that earn the cost of capital and the third by making investments that earn less than the cost of capital.

It is this perspective on growth that makes me skeptical about companies that grow through acquisitions, especially when those acquisitions are big and are of public companies. Since you have to pay market price plus (a premium of 20-30%) to acquire a public company, for a growth-motivated acquisition to create value, you have to be able to find a growth company that is under valued by more than 20% or 30%, given its growth rate, at the time that you initiate the deal to be able to walk away with value added. Note that, much as I am tempted to do a riff about the wondrous benefits of bringing both Botox and Viagra under one corporate entity, I am deliberately keeping synergy out of the equation since it can justify a premium.

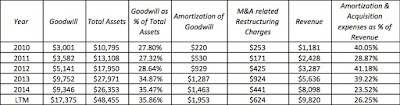

Let's consider then the proposition that the Pfizer deal for Allergan is driven by the motivation of buying growth. The basis for the story is visible in this comparison of Pfizer and Allergan's operating numbers over the last five years:

Over these five years, Pfizer's revenues shrank about 6% a year whereas Allergan's revenues grew at 40.62% a year. That makes the case for the acquisition, right? Not quite, because it depends on whether the market is already pricing in Allergan's growth. If it is, buying Allergan will allow Pfizer to grow faster, but not create value and may in fact destroy value if the premium paid is large enough. To examine whether Allergan offers growth at a bargain, I considered valuing Allergan, but very quickly abandoned the idea, because it reminded me of Valeant, insofar as it has grown rapidly through acquisitions, funded with significant amounts of debt and its financial statements are a mess. Thus, while it clear that Allergan has grown fast, the question of whether it has grown sensibly is a question that remains to be answered. Looking at the multiples at which Allergan was trading, prior to the Pfizer bid, there is almost no multiple on which it looks like a bargain.

| Pharmaceuticals | Allergan | Allergan Premium | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PE Ratio | 31.24 | NA | NA |

| Price/Book Equity | 4.11 | 4.37 | 6.33% |

| EV/EBIT | 20.12 | 53.15 | 164.17% |

| EV/EBITDA | 13.97 | 19.32 | 38.30% |

| EV/EBITDAR | 9.71 | 16.58 | 70.75% |

| EV/Sales | 4.71 | 7.85 | 66.67% |

What is the bottom line? If I were a Pfizer stockholder, I would be concerned if buying growth were the primary reason for this acquisition, since the growth at Allergan is not only at a premium price but also untested (insofar as it is acquired growth rather than organic growth). I would be terrified, especially after recent scares, that the acquisition accounting at the company may be hiding bad surprises.

The Insanity of the US Tax Code

One of the most surprising aspects of this deal is how open the Pfizer management has been about the tax motivations for the deal, with Ian Read, the CEO of Pfizer, saying that "the company is at a tremendous disadvantage under the U.S. corporate tax code and that Pfizer is competing against foreign companies with one hand tied behind our back.” This planned "inversion", of course, has triggered a heated response, understandable (at least politically), though some of the critics don't quite understand the US tax law and what exactly Pfizer will gain by leaving behind its US incorporation.

I have vented extensively about the absurdity of US tax law and how it encourages perverse behavior from businesses (and individuals). Rather than repeat myself, let me focus in on the three aspects of the law that makes it so damaging:

- The level of rates: There was a time four decades ago when the US federal corporate tax rate, at 40%, was in the middle of the global tax rate distribution, with many countries adopting a policy of punitive corporate taxation. The corporate tax rate in the US was last lowered in 1986 to 34%, then raised to 35% in 1993 and has remained unchanged since. With state and local taxes, it amounts to close to 40% in 2015. The rest of the world has moved away from the US and lowered corporate tax rates, leaving it with one of the highest marginal tax rates in the world in 2015. (See this KPMG site for tax rates around the world)

Source: KPMG - Global versus Territorial taxation: Adding to the US tax code's woes is the requirement that US companies pay the US tax rate not just on US income but on income generated elsewhere in the world. In 2015, it remains one of six countries that follow this practice, whereas the rest of the world has moved to a territorial tax model, where companies get taxed based on where they generate income (and are done). The Global tax model, which was born in an age when the US economy was the driver of the global economy and US companies were domestically focused, results in US multinationals facing much higher tax rates on world income than multinationals incorporated elsewhere. (Interestingly, Ireland is one of the six countries with a global tax model but with its low tax rate, the effect is muted.)

- The Repatriation Trigger: To cap off this trifecta, US tax law adds a clause that specifies that the “additional US tax” due on foreign income has to be paid only when that income is repatriated to the United States. In response, US companies have had the logical reaction and not repatriated foreign income, leaving that income “trapped” in foreign locales. In 2015, it was estimated that the trapped cash amounted to more than $2 trillion, money that cannot be used to pay dividends, buy back stock or make investments in the US, but can be used to make investments anywhere else in the world.

- No US taxes on foreign income: While the company will continue to pay the US tax rate on its US income, its foreign income will be taxed only at the foreign domicile's tax rate.

- Untrap cash: To the extent that the company has built up trapped earnings (in foreign locales) that it is restricted from using, it can release the cash without any tax penalties.

Pfizer: The Numbers

To understand how exposed Pfizer is to the vagaries of US tax law, I started by looking at the geographical distribution of Pfizer revenues over time:

Note that Pfizer generated only 43.08% of its revenues in the first nine months of 2015. If Pfizer were to be taxed, at the marginal rate in each region, based on where it generated its revenues (regional tax), its tax rate in those nine months would have been 30.68%. As a US company, though, Pfizer would have to pay almost 40% of this income as taxes, translating into significantly higher taxes each period. Pfizer, of course, chose not to take this course, as manifested in two numbers. The effective tax rate that Pfizer has paid over the last five years has averaged to 23.45%, well below 40%, and a significant portion (my rough estimate is $12 billion) of Pfizer’s cash balance of $20.66 billion is trapped. Binging it back will result in a tax bill of $1.99 billion (using a differential tax rate of 16.55%, the difference between the US marginal tax rate of 40% and the effective tax rate of 23.45%).

Valuing Pfizer

To illustrate the impact that changing the tax code that governs Pfizer has on its value, I considered three scenarios.

- Patriot Games: In this scenario, I assume that Pfizer does its patriotic duty (as some critics would label it) and not only decide to bring all of its trapped cash home today (and pay the differential taxes) but repatriate all of its foreign income each year back to the US and pay a 40% marginal tax rate on that income.

- Wait-it-out (Tax Limbo): In this scenario, Pfizer will leave its trapped cash overseas, continue to pay taxes to foreign governments on foreign income but not repatriate the cash. That will leave their effective tax rate well below the US marginal tax rate and Pfizer will have to hope that US tax law gets fixed or that Congress does another one of its “once in a lifetime” tax holidays.

- Go Irish: In this scenario, Pfizer buys Allergan and meets the requirements for shifting its incorporation to Ireland. Note that doing so does not affect their taxes on US income but it will not only un-trap their cash but also remove the constraint they face today on foreign income.

The different assumptions that I make about taxes under the three scenarios are summarized:

| Tax Model | Marginal tax rate (for cost of debt) | Effective tax rate (next 10 years) | Effective tax rate (in stable growth) | Trapped Cash |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patriot Games | 40% | 40% | 40% | Return immediately & pay taxes now. |

| Wait-it-out (Tax Limbo) | 40% | 23.45%, with taxes on deferred taxes paid in year 10. | 40% | Return in ten years & pay taxes then. |

| Go Irish (Invert) | 40% | 23.45% | 30.68% | No taxes due |

In the table below, I value Pfizer under each scenario (see spreadsheet), first using the conventional accounting numbers (which treat R&D as an operating expenses) and next using adjusted numbers (where I capitalize R&D):

The rationale for an inversion is that it will increase Pfizer’s equity value by $27.2 billion and its share price by $4.69 per share. This calculation, though, is based on the assumption that US tax law will never change, and that its dysfunctional components will continue in perpetuity. If you assume that the current bipartisan talk of fixing the law will result in changes (in either the corporate tax rate or in the global tax feature), the value increase will drop off substantially.

Deal or No Deal?

I applaud Ian Read's focus on shareholder value but will this deal create that value? I am skeptical and here is why. Even if you accept the upper limit of the value of inversion ($27.2 billion), that increase in value does not incorporate two potential costs associated with inversion.

| Patriot Games | Wait-it-out | Go Irish | Effect of Inversion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R&D Expensed | Equity Value | $154,806.00 | $176,047.00 | $209,637.00 | $33,590.00 |

| Per share | $25.09 | $28.53 | $34.39 | $5.86 | |

| R&D capitalized | Equity Value | $121,074.00 | $135,156.00 | $162,309.00 | $27,153.00 |

| Per share | $19.62 | $21.91 | $26.60 | $4.69 |

The rationale for an inversion is that it will increase Pfizer’s equity value by $27.2 billion and its share price by $4.69 per share. This calculation, though, is based on the assumption that US tax law will never change, and that its dysfunctional components will continue in perpetuity. If you assume that the current bipartisan talk of fixing the law will result in changes (in either the corporate tax rate or in the global tax feature), the value increase will drop off substantially.

Deal or No Deal?

I applaud Ian Read's focus on shareholder value but will this deal create that value? I am skeptical and here is why. Even if you accept the upper limit of the value of inversion ($27.2 billion), that increase in value does not incorporate two potential costs associated with inversion.

- The new rules covering inversions will require that Pfizer go through contortions to qualify and some of these contortions will add to the cost of the deal.

- There is the possibility of a backlash, not so much from customers, but from politicians. There are senators who are already threatening the company with consequences, though I am not sure that any of them would actually go as far as to ban or restrict Pfizer product sales in the US (since that would hurt those who need the drugs the most). Even if they do, given that the US Senate is disproportionately composed of older men, I am confident that they will carve out a "Viagra exception" for themselves.

There is a second and even bigger concern that I would have as a Pfizer stockholder. If the rumors that Pfizer is planning to pay a 30% premium are right, that would translate into a premium of more than $30 billion over Allergan's market capitalization to buy the company. Since the growth is already priced in (at least in my view), the only way you can create value is to draw on synergy and nothing that either company has said suggests any concrete benefits from the combination.

The bottom line is that this looks like a bad deal for the wrong company, at the wrong time and at the wrong price, the wrong company because Allergan's accounting statements are a mine field due to acquisition accounting, the wrong time because we may actually be on the verge of a major change in US corporate tax code and at the wrong price because of the premium on an already large market capitalization.

The bottom line is that this looks like a bad deal for the wrong company, at the wrong time and at the wrong price, the wrong company because Allergan's accounting statements are a mine field due to acquisition accounting, the wrong time because we may actually be on the verge of a major change in US corporate tax code and at the wrong price because of the premium on an already large market capitalization.

The Morality Play?

As I was writing this post last week, I had a conversation with a friend about Pfizer. After I explained why I thought the Pfizer plan to acquire Allergan made sense, given the tax code and Pfizer's global exposure, her response was that Pfizer should not do this because “it is immoral". While I was floored initially by her assertion, it would be have been both futile and hubristic for me to try to prove her wrong. She is entitled to her moral judgments, just as I am entitled to mine, but it is moral, rather than economic, differences that usually lie at the heart of tax debates and that is perhaps why it is so difficult to get a consensus.

If you own a business that would benefit from shifting away from the US for tax reasons, and you have patriotic or moral reasons for not doing so, you are well within your rights in staying US-bound and I support you in your choice. If you are the manager of a publicly traded company and you face the same choice, I am afraid that you cannot impose your patriotic or moral judgments on your stockholders. Not only are many of them foreign investors (with a very different sense of what comprises patriotism), but quite a few of them will part ways with you on your judgment that maximizing taxes paid to the government is a moral calling.

YouTube Video

Blog Posts in this series

If you own a business that would benefit from shifting away from the US for tax reasons, and you have patriotic or moral reasons for not doing so, you are well within your rights in staying US-bound and I support you in your choice. If you are the manager of a publicly traded company and you face the same choice, I am afraid that you cannot impose your patriotic or moral judgments on your stockholders. Not only are many of them foreign investors (with a very different sense of what comprises patriotism), but quite a few of them will part ways with you on your judgment that maximizing taxes paid to the government is a moral calling.

YouTube Video

Blog Posts in this series

- Divergence in the Drug Business: Pharmaceuticals and Biotechnology

- Checkmate or Stalemate? Valeant's Fall from Grace

- Runaway Stories and Fairy Tale Endings: The Theranos Lesson

- Value and Taxes: Breaking down the Pfizer- Allergan Deal

Spreadsheets