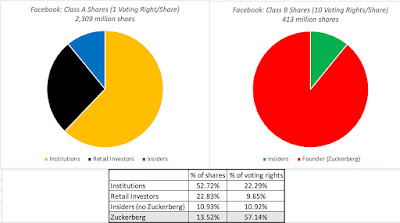

In my first two posts on Facebook, I noted that its most recent earnings report, and the market reaction to it, offers an opportunity for us to talk about bigger issues. I started by examining corporate governance, or its absence, and argued that some of the frustration that investors in Facebook feel about their views being ignored can be traced to a choice that they made early to give up the power to change management, by acquiescing to dual class shares. Facebook, I argued, is a corporate autocracy, with Mark Zuckerberg at its helm. In the second post, I pointed to inconsistencies in how accountants classify operating, capital and financing expenses, and the consequences for reported accounting numbers. Some of the bad news in Facebook's earnings report, especially relating to lower profitability, reflected accounting mis-categorization of R&D and expenses at Reality Labs (Facebook's Metaverse entree) as operating, rather than capital expenses. In fact, I concluded the post by arguing that investors in Facebook were pricing in their belief that the billions of dollars the company had invested in the Metaverse would be wasted, and argued that Facebook faced some of the blame, for not telling a compelling story to back the investment. In this post, I want to focus on that point, starting with a discussion of why stories matter to investors and traders and the story that propelled the company to a trillion-dollar market capitalization not that long ago. I will close with a look at why business stories can break, change and shift, focusing in particular on the forces pushing Facebook to expand or perhaps even change its story, and whether the odds favor them in that endeavor.

Narrative and Value

As someone who has spent the last four decades talking, teaching and doing valuation that we have lost our way in valuation. Even as data has become more accessible and our tools have become more powerful, it is my belief that the quality of valuations has degraded over time. One reason is that valuation, at least as practiced, has become financial modeling, where Excel ninjas pull numbers from financial statements, put them into spreadsheets and extrapolate based upon past trends. Along the way, we have lost a key component of valuation, which is that every valuation tells a business story, and understanding what the story is and its weakest links is key to good valuation,

The Connection

In the first session of my valuation class, I pose a question, "What comes more naturally to you, telling a story or working with numbers?", and I very quickly add that there is no right answer that I am looking for. That is because the answer will vary across people, with some exhibiting a more natural tendency towards story-telling and others towards working with numbers. In my valuation classes, the selection bias that leads people to come back to business school, and then to pick the valuation class as an elective, also results in the majority picking the "numbers" side, though I am glad to say that I have enough history majors and literature buffs to create a sizable "story" contingent. In the immediate aftermath, I then put forth what I believe is one of the biggest hidden secrets in valuation, which is that a good valuation is not just numbers on a spreadsheet, which is the number-crunching vision, or a big business story, which is the story-tellers' variant, but a bridge between stories and numbers:

Stories + Numbers: The Symbiosis

The challenge in valuation, and it has only become worse in time, is that the divide between story tellers and number crunchers has only become wider over time, and has reached a point where each side not only does not understand the other, but also views it with contempt. Venture capitalist, raised on a diet of big stories and total addressable markets has little in common with bankers, trained to think in terms of EV to EBITDA multiples and accounting ROIC, and when put in a room together, it should come as no surprise that they find each other's language indecipherable. At the risk of being shunned by both groups, I will argue int his section that each side will benefit, from learning to understand and use the tools of the other side.

1. Why stories matter in a numbers world

If you are a numbers valuation, you start with some advantages. Not only will you find financial statements easier to disentangle, but you will also be able to develop a framework for converting these numbers to forecasts fairly easily. In other words, you will have no trouble creating something that looks like a legitimate valuation, with numbers details and an end value, even if that value is nonsensical. With a just-the-numbers valuation, there are four dangers that you face:

- Play with numbers: When a valuation is all about the numbers, it is easy to start playing with the numbers, unconstrained by any business sense, and change the value. It is not uncommon to see analysts, when they estimate a value that they think is "too low", to increase the revenue growth rate for a company, holding all else constant, and increase the value to what they would "like it to be".

- False precision: Number crunchers love precision, and the pathways they adopt to get to more precise valuations are often counter-productive, in terms of delivering more accurate valuations. From estimating the cost of capital to the fourth decimal point to forecasting all three accounting statements (income statements, balance sheet and statement of cashflows), in excruciating detail, for the next 20 years, analysts lose the forest for the trees, and produce valuations that look precise, but are not even close to being estimates of true value.

- Drown in data: If the complaint that analysts in the 1970s and even the 1980s might have had is that there was not enough data, the complaint today, when they value companies, is that there is too much data. That data is not only quantitative, with company disclosures running to hundreds of pages and databases that cover thousands of companies, but also qualitative, as you can access every news story about a company over its history, and in real time. Without guard rails, it is easy to see why this data overload can overwhelm investors and analysts, and lead them, ironically, to ignore most of it.

- Denial of biases: It is almost impossible to value a business without bias, with some bias coming from what you know about the business and some coming from whether you are getting paid to do the valuation, and how much. In a valuation driven entirely with numbers, analysts can fool themselves into believing that since they work with numbers, they cannot be biased, when, in fact, bias permeates every step in the process, implicitly or explicitly. Put simply, there are very facts in valuation and lots of estimates, and if you are making those estimates, you are bringing your biases

- Stories are memorable, numbers less so: Even the most-skilled number cruncher, aided and abetted with charts and diagrams, will have a difficult time creating a valuation that is even close to being as good a compelling business story, in hooking investors and being memorable. I believe that long after my students have forgotten what growth rates and margins I assumed in the valuation of Amazon that I showed them in 2012, they will remember my characterization of Amazon as my "field of dreams company", built on the premise that if they build it (revenues), they (profits) will come.

- Stories allow for consistency-tests: When your valuation numbers come from a story, it becomes almost impossible to change one input to your valuation without thinking through how that change affects your story. An increase in revenue growth, in a company in a niche market with high margins, may require a recalibration of the story to make it a more mass-market story, albeit with lower margins.

- Stories allow you to screen and manage data: Having a valuation story that binds your numbers together and yields a value also allows you a framework for separating the data that matters (information) from the data that does not (distractions), and for organizing that data.

- Stories lead to business follow-through: If you are a business-owner, valuing your own business, understanding the story that you are telling in that valuation is extraordinarily useful in how you run the business. Thus, if you want to follow Amazon's path to the Field of Dreams, your business strategy should be built around expanding your market and increasing revenues, while also mapping out a pathway to eventually monetizing those markets and gaining access to enough capital to be able to do so.

2. Why numbers matter in a story world

I am not a story-telling natural, but I have tried to look at valuation, through the eyes of story tellers, over the last few years. Again, you start with some advantages, as a skilled story teller, especially if you also have the added benefit of charisma. You can use your story telling skills to draw investors, employees and the rest of the world into your story, and if you frame it well, you may very well be able to evade the type of scrutiny that comes with numbers. There are dangers, though, including the following:

- Fairy tales: Without the constraint of business first principles or explicit numbers about key inputs, you can tell stories of unstoppable growth and incredible profits for your company that are alluring, but impossible. If you are a con man, that is your end game, but even if you are not a con man, it is easy to start believing your own tall stories about businesses. As you watch the unraveling of FTX, you have to wonder whether Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF) set out to create a crypto-based Ponzi scheme, or whether this is the end result of a business story that was unchecked by any of the big name investors who participated into its growth.

- Anecdotal evidence: Story tellers tend to gravitate towards anecdotal data that supports their valuation stories. Rather than drown in the data overflow world we live in, story tellers pick and choose the data that best fits their stories, and use them to good effect, often fooling themselves about viability and profitability along the way.

- Unconstrained biases: If number crunchers are in denial about their biases, story tellers often revel in their biases, presenting them as evidence of the conviction that they have in their stories. Using the FTX example again, SBF was open about his belief that the future belonged to crypto, and that his entire business was built on that belief, and to his audience, composed of other true crypto-believers, this was a plus, not a minus.

- Numbers give credibility to stories: As we noted in the last section, stories are hooks that draw others to a business idea, but it may not be enough to get them to invest their money in it. For that to happen, you may have to use numbers to augment and back up your business story to give it credibility and create enough confidence that you have the business sense to make it succeed.

- Numbers allow for plausibility checks: If you are on the other side of a valuation pitch, especially one built almost entirely around a story, the absence of numbers can make it difficult to take the story through the 3P test, where you evaluate whether it is possible, plausible and probable. It is your obligation as an investor to push for specificity, often in terms of the market that the business is targeting and the market share and profitability numbers that will determine its profitability. Again, business owners and analysts who can respond to this demand for specifics and numbers are more likely to get the capital that they seek.

- Number create accountability: For business owners and managers, the use of numbers allows for accountability, where your actual numbers on total market size, market share and profitability can be compared to your forecasts. While that lead to uncomfortable findings, i.e., that you delivered below your expectations, it is an integral part of building a successful business over time, since what you learn from the feedback can allow you to alter, modify and sometimes replace business models that are not working well.

The Facebook Narrative

In the last few months, as Facebook has collapsed, investors seem to have forgotten about its astonishing climb in the decade prior, with market capitalization increasing from $100 billion at its IPO in 2012 to its trillion-dollar capitalization in July 2021. In my view, a key factor behind the stratospheric rise was the valuation story told by and about the company, and the story's appeal to investors.

The Facebook Story

The core of the Facebook story is its mammoth user base, especially if you include Instagram and WhatsApp as part of the Facebook ecosystem, but if that is all you focused on, you would be missing large parts of its appeal. In fact, the Facebook story has the following constituent parts:

- Billions of intense users: If there is one lesson that we should have learned from our experiences with user-based and subscriber-based companies over the last decade, it is that not all users or subscribers are created equal. With Facebook, it is not just the roughly three billion people who are in its ecosystem that should draw your attention, but the amount of time they spend in it. Until TikTok recently supplanted it at the top, Facebook had the most intense user base of any social media platform, with users staying on the platform roughly an hour a day in 2019.

- Sharing personal data in their postings: As a platform that encourages users to share everything with their "friends", it is undeniable that Facebook has accumulated immense amounts of data about its users. If you are a privacy purist, and you find this unconscionable, it is worth noting that these users were not dragged on to a platform and forced to share their deeply personal thoughts and feelings, against their wishes.

- Which could be utilized to focus advertising at them: In 2018, at the peak of the Cambridge Analytica scandals, when people were piling on Facebook for its invasion of privacy, I noted invading user privacy, albeit with their tacit approval, lies at the core of Facebook's success in online advertising. In short, Facebook uses what it has learnt about the people inhabiting its platform to focus advertising to them.

- In a world where online ads were consuming the advertising business: Facebook also benefited from a macro shift in the advertising business, where advertisers were shifting from traditional advertising modes (newspapers, television, billboards etc.) to online advertising; online advertising increased from less than 10% of total advertising in 2005 to close to 60% of total adverting in 2020.

And its appeal

Every business, especially in its youth, markets itself with a story and it is worth asking why investors took to Facebook's story so quickly and attached so much value to it.

- Simple and easy to understand: In telling business stories, I argue that it pays to keep the story simple and to give it focus, i.e., lay out the pathways that the story will lead the company to make money. Facebook clearly followed this practice, with a story that was simple and easy for in investors to understand and to price in. Just to provide a contrast, consider how much more difficult it is for Palantir or Snowflake to tell a business story that investors can grasp, let alone value.

- Personal experiences with business: Adding to the first point, investors feel more comfortable valuing businesses, where they have sampled the products or services offered by these businesses and understand what sets them apart (or does not) from the competition. I would wager that almost every investor, professional or retail, who invested in Facebook has a Facebook page, and even if they do not post much on the page, have seen ads directed specifically at them on that page.

- Backed up by data: In the last decade, we have seen other companies with simple stories that we have personal connections to, like Uber, Airbnb and Twitter, go public, but none of them received the rapturous response that Facebook did, at least until July 2021. The reason is simple. Unlike those companies, Facebook, from day one as a public company, has been able to back its story up with numbers, both in terms of revenues and profitability, as can be seen in the graph below, where I look at its revenues and operating profits from 2012 to 2021:

Narrative Changes and Resets

The value of a business is, in large part, driven by your story for the business, but that story will change over time, as the business, the market it is in and the macro environment change. In some cases, the story can get bigger, leading to higher value, and in some, it can get smaller, and we will begin by looking at why business stories change, and classify those changes, before looking at the Facebook story.

Narrative Breaks, Changes and Shifts

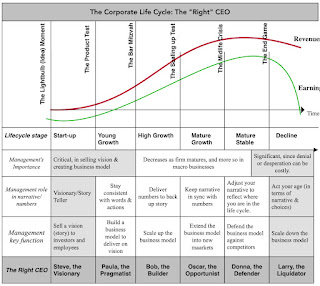

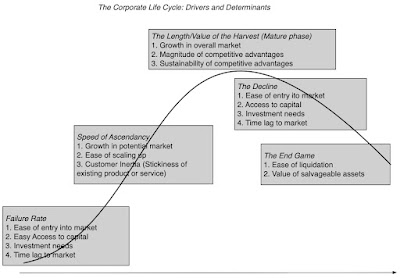

If business stores change over time, what form will that change take? To answer the question, I broke down business story changes into three groups, with the proviso that there are some business changes that fall into more than one group:

- Story breaks: The most consequential value change comes from a story break, where a key component of a business story breaks, sometimes due to external factors and sometimes due to miscalculations and missteps on the part of the management of the company. In the former group, we would include acts of God (terrorism, a hurricane or COVID) and regulatory or legal events (failure to get regulatory approval for a drug, for a pharmaceutical company) that put an end to a business model. In the latter, we would count companies where management pushed the limits of the law to breaking point and beyond, damaging its reputation to the point that it cannot continue in business.

- Story shifts: At the other end of the spectrum are story shifts, where the core business model remains intact, but its contours (in terms of growth, profitability and risk) change, as the result of market changes (market growth surges, slows or stalls), competitive dynamics (a competitor introduces a new product or withdraws an existing one) or technology (working in favor of the story or against it). Note the resulting changes in value can be substantial, and in either direction, depending on how and how much the valuation inputs change as a result of the story shift.

- Story changes: Finally, there are story changes, where a company augments an existing business story by investing in or acquiring a new business, shrinks its existing business by withdrawing or divesting an existing business or product or attempts a story reset or rebirth, by replacing an existing business story with a new one.

I summarize these possible story alterations in the picture below:

As you can see from the types of changes that can occur, some business story changes are triggered by external forces, and can be traced to changes in macroeconomic conditions, country risk or regulatory/legal structures, some business story changes are the result of management actions, at the company or at its competitors and some business story changes are the consequence of a company scaling up and/or aging. It is worth noting that disruption, at its core, creates changes to a sector or industry that can break some status-quo businesses, while creating new ones with significant value.

Facebook: A Narrative Reset?

In the last section, we looked at the incredible success that Facebook had between 2012 and 2021 with its user-driven, online advertising business model, both in terms of market capitalization (rising from $100 billion to $ 1 trillion) and in terms of operating results. You may wonder why a company that has had this much success with its story would need to change, but the last year and a half is an indication of how quickly business conditions can change.

Forces driving a reset

Facebook's original business story was built on two premises, with the first being the use of data that it obtained on its customers to deliver more focused advertisements and the second being the rapid growth in the online advertising business, largely at the expense of traditional advertising. Both premises are being challenged by developments on the ground, and as they weaken, so is the pull of the Facebook story.

- On the privacy front, the Cambridge Analytica episode, though small in its direct impact, cast light on an unpleasant truth about the Facebook business model, where the invasion of user privacy is a feature of its business story, not a bug. Put differently, if Facebook decides not to use the information that you provide it, in the course of your postings, in its business model, a large portion of its allure to advertisers disappears.

- The halcyon days of growth in the online advertising market are behind us, as it acquires a dominant share of overall advertising, and starts growing at rates that reflect growth in total advertising. As one of the two biggest players in the market, with Google being the other one, Facebook does not have much room on the upside for growth.

Choices for the company

Faced with slower revenue growth and concerned about the effect that privacy regulations in the EU and the US will alter its business model, Facebook has been struggling with a way forward. As I see it, there were three choices that Facebook could have made (though we know, in hindsight, which one they picked):

- Acceptance: Accept the reality that they are now a mature player in a slow-growth business (online advertising), albeit one in which they are immensely profitable, and scale back growth plans and spending. While this may strike some as giving up, it does provide a pathway for Facebook to become a cash cow, investing just enough in R&D to keep its existing business going for the foreseeable future, while returning huge amounts of cash to its investors each year (as dividends or buybacks).

- Denial: View the slowdown in growth in the online adverting market as temporary, and stay with its existing business model, built around aggressively seeking to gain market share from both traditional players in the advertising market and smaller online competitors. With this path, the company may be able to post higher revenue growth than if it follows the acceptance path, but perhaps with lower operating margins and more spending on R&D, if market growth is leveling off.

- Rebirth: The choice with the most upside as well as the greatest downside is for Facebook to try to reinvent itself in a new business. That may require substantial reinvestment to enter the business, and hopefully draw on Facebook’s biggest strength, i.e., its intense and mammoth user base.

What's the story?

Facebook’s plans to invest tens of billions in the Metaverse makes it an expensive venture, by any standards, and there are some who suggest that it is unprecedented, especially in technology, which many view as a capital-light business. That perception, though, collides with reality, especially when you look at how much big tech companies have been willing to invest to enter new businesses, albeit with mixed results.

- Microsoft invested $15 billion for its entry in 2015 into Azure, its cloud business, and it has invested tens of billions in data centers since, expanding its reach. That investment has paid off both quickly and lucratively, and has played a role in Microsoft's rise in market capitalization.

- Google, renamed itself Alphabet in 2015, in a well-publicized effort to rebrand itself as more than just a search engine, and has invested tens of billions of dollars in its other businesses since, but with a payoff primarily in its cloud business, which generated $19.2 billion in revenues in 2021. Just to provide a measure of how its other bets are still lagging, Google generated only $753 million in revenues from its other businesses in 2021, almost unchanged from its revenues in 2019 and 2020.

- Amazon has also invested tens of billions in its other businesses, with its biggest payoff coming in the cloud business (notice a pattern here). It has much less to show for its investments in Alexa and entertainment, and it is estimated to have lost $5 billion on its Alexa division in 2021 and spent $13 billion on new content for Amazon video.

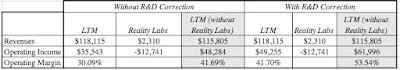

- I used the company's actual operating income from its online advertising business from the last twelve months, weighed down as they are from a slowing economy and a stronger economy, and assumed no growth and a remaining life of 20 years for the business, with a zero liquidation value at the end of year 20.

- I assumed that the company will continue to spend R&D at the same scorching rate that it set in the last twelve months, where it spent just over $32 billion on R&D, for the next 20 years.

- I also assumed that not only will Facebook to lose $10 billion a year on the Metaverse, but also that this will continue for the next decade and beyond, with no payoff in terms of increased revenues or earnings from this spending.

- I assume that Facebook is a risky company, falling at the 75th percentile of all US companies in terms of risk, and give it a cost of capital of 9%.

|

| Download spreadsheet |

- Tell with a business story for the Metaverse: Investors do not have a clear sense of what the Metaverse is, and more importantly, the business opportunities that exist in that space. Facebook needs to fill in that gap with a business story for its investments, laying out what is sees as a pathway to making money in that virtual world, as well as the strengths it will bring to delivering value on this path. I am sure that Facebook is much more qualified than I am to frame this story, but just in case they could use some guidance, here are a few possible Metaverse business models:

Of these choices, advertising clearly is the most logical extension of their existing business, but it also offers the least upside, since the company is already a dominant player in the online ad business. The acquisition of Oculus and the VR headsets that Facebook sells give it a foothold in the hardware business, but hardware is a business with lower margins and limited market size. The most lucrative story, in my view, is a ecosystem story, where Facebook gains a dominant share of the virtual world, and takes a slice of any business (transactions, gaming, subscriptions) done in that world, mirroring what Apple has done in its iPhone ecosystem. It is worth remembering that the audience that you are trying to sell this business story to is not the audience that you will be seeking out in the Metaverse, which would imply that your story should be less about technology and more about business. (I may be old and cranky. I have zero interest in the virtual world, but as a Facebook investor, I would be interested to learn its business model for this world.) - Build in specifics into your investment story: Facebook has been clear about its plans to invest billions in its new businesses, but rather than just emphasizing the total amount that it plans to make, it would be better served connecting its investment plans with the business story being told. If nothing else, it would be useful to know how much of the $12 billion spent in Reality Labs was spent on people, on technology, on software and in making better VR glasses and why all of this spending is bringing the company closer to a money-making business model.

- With markers on operating payoffs: I know that there are huge uncertainties overhanging these investments, but it would still make sense to give rough estimates of how Facebook expects revenues and operating margins to evolve on its Metaverse investment, over time. That will give investors and managers targets to track, as the company delivers results, and use the results (positive or negative) to make changes in the way future investments are made.

- And escape hatches, if things don't work out: While many companies refuse to talk about what their plans are, if a business does not pan out, viewing it as a sign of weakness or lack of conviction, I believe that Facebook will be best served if they are open about what can go wrong with their Metaverse bet, and not only about what they are doing to protect themselves, if it happens, but also exit plans, if they decide to walk away. After all, if the market is already assuming the worst, as it was just a couple of weeks ago, how can any scenario you present, no matter how negative, worsen your market standing?

- Facebook (Meta) Lesson 1: Corporate Governance

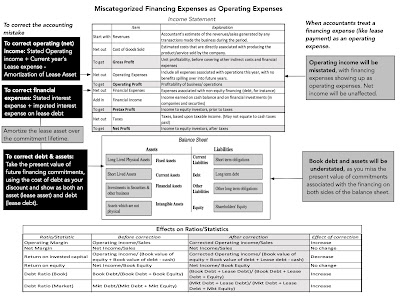

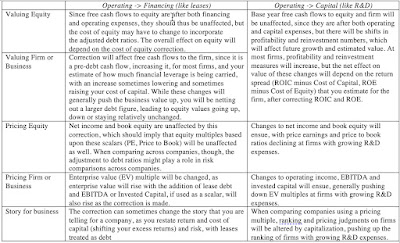

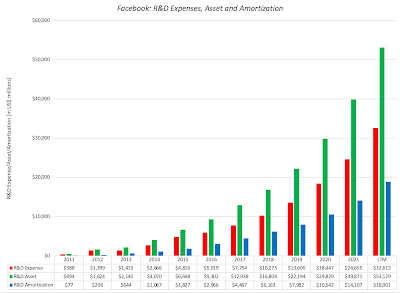

- Facebook (Meta) Lesson 2: Accounting inconsistencies and consequences

- Facebook (Meta) Lesson 3: Tell me a story!