In the context of valuing companies, and sharing those valuations, I do get suggestions from readers on companies that I should value next. While I don't have the time or the bandwidth to value all of the suggested companies, a reader from Iceland, a couple of weeks ago, made a suggestion on a company to value that I found intriguing. He suggested Blue Lagoon, a well-regarded Icelandic Spa with a history of profitability, that was finding its existence under threat, as a result of volcanic activity in Southwest Iceland. In another story that made the rounds in recent weeks, 23andMe, a genetics testing company that offers its customers genetic and health information, based upon saliva sample, found itself facing the brink, after a hacker claimed to have hacked the site and accessed the genetic information of millions of its customers. Stepping back a bit, one claim that climate change advocates have made not just about fossil fuel companies, but about all businesses, is that investors are underestimating the effects that climate change will have on economic systems and on value. These are three very different stories, but what they share in common is a fear, imminent or expected, of a catastrophic event that may put a company's business at risk.

Deconstructing Risk

While we may use statistical measures like volatility or correlation to measure risk in practice, risk is not a statistical abstraction. Its impact is not just financial, but emotional and physical, and it predates markets. The risks that our ancestors faced, in the early stages of humanity, were physical, coming from natural disasters and predators, and physical risks remained the dominant form of risk that humans were exposed to, almost until the Middle Ages. In fact, the separation of risk into physical and financial risk took form just a few hundred years ago, when trade between Europe and Asia required ships to survive storms, disease and pirates to make it to their destinations; shipowners, ensconced in London and Lisbon, bore the financial risk, but the sailors bore the physical risk. It is no coincidence that the insurance business, as we know it, traces its history back to those days as well.

I have no particular insights to offer on physical risk, other than to note that while taking on physical risks for some has become a leisure activity, I have no desire to climb Mount Everest or jump out of an aircraft. Much of the risk that I think about is related to risks that businesses face, how that risk affects their decision-making and how much it affects their value. If you start enumerating every risk a business is exposed to, you will find yourself being overwhelmed by that list, and it is for that reason that I categorize risk into the groupings that I described in an earlier post on risk. I want to focus in this post on the third distinction I drew on risk, where I grouped risk into discrete risk and continuous risk, with the later affecting businesses all the time and the former showing up infrequently, but often having much larger impact. Another, albeit closely related, distinction is between incremental risk, i.e., risk that can change earnings, growth, and thus value, by material amounts, and catastrophic risk, which is risk that can put a company's survival at risk, or alter its trajectory dramatically.

There are a multitude of factors that can give rise to catastrophic risk, and it is worth highlighting them, and examining the variations that you will observe across different catastrophic risk. Put simply, a volcanic eruption, a global pandemic, a hack of a company's database and the death of a key CEO are all catastrophic events, but they differ on three dimensions:

- Source: I started this post with a mention of a volcano eruption in Iceland put an Icelandic business at risk, and natural disasters can still be a major factor determining the success or failure of businesses. It is true that there are insurance products available to protect against some of these risks, at least in some parts of the world, and that may allow companies in Florida (California) to live through the risks from hurricanes (earthquakes), albeit at a cost. Human beings add to nature's catastrophes with wars and terrorism wreaking havoc not just on human lives, but also on businesses that are in their crosshairs. As I noted in my post on country risk, it is difficult, and sometimes impossible, to build and preserve a business, when you operate in a part of the world where violence surrounds you. In some cases, a change in regulatory or tax law can put the business model for a company or many company at risk. I confess that the line between whether nature or man is to blame for some catastrophes is a gray one and to illustrate, consider the COVID crisis in 2020. Even if you believe you know the origins of COVID (a lab leak or a natural zoonotic spillover), it is undeniable that the choices made by governments and people exacerbated its consequences.

- Locus of Damage: Some catastrophes created limited damage, perhaps isolated to a single business, but others can create damage that extends across a sector geographies or the entire economy. The reason that the volcano eruptions in Iceland are not creating market tremors is because the damage is likely to be isolated to the businesses, like Blue Lagoon, in the path of the lava, and more generally to Iceland, an astonishingly beautiful country, but one with a small economic footprint. An earthquake in California will affect a far bigger swath of companies, partly because the state is home to the fifth largest economy in the world, and the pandemic in 2020 caused an economic shutdown that had consequences across all business, and was catastrophic for the hospitality and travel businesses.

- Likelihood: There is a third dimension on which catastrophic risks can vary, and that is in terms of likelihood of occurrence. Most catastrophic risks are low-probability events, but those low probabilities can become high likelihood events, with the passage of time. Going back to the stories that I started this post with, Iceland has always had volcanos, as have other parts of the world, and until recently, the likelihood that those volcanos would become active was low. In a similar vein, pandemics have always been with us, with a history of wreaking havoc, but in the last few decades, with the advance of medical science, we assumed that they would stay contained. In both cases, the probabilities shifted dramatically, and with it, the expected consequences.

Business owners can try to insulate themselves from catastrophic risk, but as we will see in the next sections those protections may not exist, and even if they do, they may not be complete. In fact, as the probabilities of catastrophic risk increase, it will become more and more difficult to protect yourself against the risk.

Dealing with catastrophic risk

It is undeniable that catastrophic risk affects the values of businesses, and their market pricing, and it is worth examining how it plays out in each domain. I will start this section with what, at least for me, I is familiar ground, and look at how to incorporate the presence of catastrophic risk, when valuing businesses and markets. I will close the section by looking at the equally interesting question of how markets price catastrophic risk, and why pricing and value can diverge (again).

Catastrophic Risk and Intrinsic Value

Much as we like to dress up intrinsic value with models and inputs, the truth is that intrinsic valuation at its core is built around a simple proposition: the value of an asset or business is the present value of the expected cash flows on it:

That equation gives rise to what I term the "It Proposition", which is that for "it" to have value, "it" has to affect either the expected cashflows or the risk of an asset or business. This simplistic proposition has served me well when looking at everything from the value of intangibles, as you can see in this post that I had on Birkenstock, to the emptiness at the heart of the claim that ESG is good for value, in this post. Using that framework to analyze catastrophic risk, in all of its forms, its effects can show in almost every input into intrinsic value:

Looking at this picture, your first reaction might be confusion, since the practical question you will face when you value Blue Lagoon, in the face of a volcanic eruption, and 23andMe, after a data hack, is which of the different paths to incorporating catastrophic risks into value you should adopt. To address this, I created a flowchart that looks at catastrophic risk on two dimensions, with the first built around whether you can buy insurance or protection that insulates the company against its impact and the other around whether it is risk that is specific to a business or one that can spill over and affect many businesses.

- Intrinsic Value Effect: If the catastrophic risk is fully insurable, as is sometimes the case, your intrinsic valuation became simpler, since all you have to do is bring in the insurance cost into your expenses, lowering income and cash flows, leave discount rates untouched, and let the valuation play out. Note that you can do this, even if the company does not actually buy the insurance, but you will need to find out the cost of that foregone insurance and incorporate it yourself.

- Pluses: Simplicity and specificity, because all this approach needs is a line item in the income statement (which will either exist already, if the company is buying insurance, or can be estimated).

- Minuses: You may not be able to insure against some risks, either because they are uncommon (and actuaries are unable to estimate probabilities well enough, to set premiums) or imminent (the likelihood of the event happening is so high, that the premiums become unaffordable). Thus, Blue Lagoon (the Icelandic spa that is threatened by a volcanic eruption) might have been able to buy insurance against volcanic eruption a few years ago, but will not be able to do so now, because the risk is imminent. Even when risks are insurable, there is a second potential problem. The insurance may pay off, in the event of the catastrophic event, but it may not offer complete protection. Thus, using Blue Lagoon again as an example, and assuming that the company had the foresight to buy insurance against volcanic eruptions a few years ago, all the insurance may do is rebuild the spa, but it will not compensate the company for lost revenues, as customers are scared away by the fear of volcanic eruptions. In short, while there are exceptions, much of insurance insures assets rather than cash flow streams.

- Applications: When valuing businesses in developed markets, we tend to assume that these businesses have insured themselves against most catastrophic risks and ignore them in valuation consequently. Thus, you see many small Florida-based resorts valued, with no consideration given to hurricanes that they will be exposed to, because you assume that they are fully insured. In the spirit of the “trust, but verity” proposition, you should probably check if that is true, and then follow up by examining how complete the insurance coverage is.

- Intrinsic Value Effect: If the catastrophic risk is not insurable, but the business will survive its occurrence even in a vastly diminished state, you should consider doing two going-concern valuations, one with the assumption that there is no catastrophe and one without, and then attaching a probability to the catastrophic event occurring.Expected Value with Catastrophe = Value without Catastrophe (1 – Probability of Catastrophe) + Value with Catastrophe (Probability of Catastrophe)In these intrinsic valuations, much of the change created by the catastrophe will be in the cash flows, with little or no change to costs of capital, at least in companies where investors are well diversified.

- Pluses: By separating the catastrophic risk scenario from the more benign outcomes, you make the problem more tractable, since trying to adjust expected cash flows and discount rates for widely divergent outcomes is difficult to do.

- Minuses: Estimating the probability of the catastrophe may require specific skills that you do not have, but consulting those who do have those skills can help, drawing on meteorologists for hurricane prediction and on seismologists for earthquakes. In addition, working through the effect on value of the business, if the catastrophe occurs, will stretch your estimation skills, but what options do you have?

- Applications: This approach comes into play for many different catastrophic risks that businesses face, including the loss of a key employee, in a personal-service business, and I used it in my post on valuing key persons in businesses. You can also use it to assess the effect on value of a loss of a big contract for a small company, where that contract accounts for a significant portion of total revenues. It can also be used to value a company whose business models is built upon the presence or absence of a regulation or law, in which case a change in that regulation or law can change value.

- Intrinsic Value Effect: If the catastrophic risk is not insurable, and the business will not survive, if the risk unfolds, the approach parallels the previous one, with the difference being that that the failure value of the business, i.e, what you will generate in cash flows, if it fails, replaces the intrinsic valuation, with catastrophic risk built in:Expected Value with Catastrophe = Value without Catastrophe (1 – Probability of Catastrophe) + Failure Value (Probability of Catastrophe)The failure value will come from liquidation the assets, or what is left of them, after the catastrophe.

- Pluses: As with the previous approach, separating the going concern from the failure values can help in the estimation process. Trying to estimate cash flows, growth rates and cost of capital for a company across both scenarios (going concern and failure) is difficult to do, and it is easy to double count risk or miscount it. It is fanciful to assume that you can leave the expected cash flows as is, and then adjust the cost of capital upwards to reflect the default risk, because discount rates are blunt instruments, designed more to capture going-concern risk than failure risk.

- Minuses: As in the last approach, you still have to estimate a probability that a catastrophe will occur, and in addition, and there can be challenges in estimating the value of a business, if the company fails in the face of catastrophic risk.

- Applications: This is the approach that I use to value highly levered., cyclical or commodity companies, that can deliver solid operating and equity values in periods where they operate as going concerns, but face distress or bankruptcy, in the face of a severe recession. And for a business like the Blue Lagoon, it may be the only pathway left to estimate the value, with the volcano active, and erupting, and it may very well be true that the failure value can be zero.

- Intrinsic Value Effect: The calculations for cashflows are identical to those done when the risks are company-specific, with cash flows estimated with and without the catastrophic risk, but since these risks are sector-wide or market-wide, there will also be an effect on discount rates. Investors will either see more relative risk (or beta) in these companies, if the risks affect an entire sector, or in equity risk premiums, if they are market-wide. Note that these higher discount rates apply in both scenarios.

- Pluses: The risk that is being built into costs of equity is the risk that cannot be diversified away and there are pathways to estimating changes in relative risk or equity risk premiums.

- Minuses: The conventional approaches to estimating betas, where you run a regression of past stock returns against the market, and equity risk premiums, where you trust in historical risk premiums and history, will not work at delivering the adjustments that you need to make.

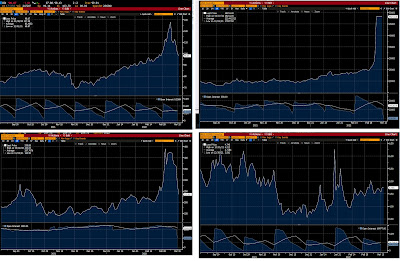

- Applications: My argument for using implied equity risk premiums is that they are dynamic and forward-looking. Thus, during COVID, when the entire market was exposed to the economic effects of the pandemic, the implied ERP for the market jumped in the first six weeks of the pandemic, when the concerns about the after effects were greatest, and then subsided in the months after, as the fear waned:

In a different vein, one reason that I compute betas by industry grouping, and update them every year, is in the hope that risks that cut across a sector show up as changes in the industry averages. In 2009, for instance, when banks were faced with significant regulatory changes brought about in response to the 2008 crisis, the average beta for banks jumped from 0.71 at the end of 2007 to 0.85 two years later.

The intrinsic value approach assumes that we, as business owners and investors, look at catastrophic risk rationally, and make our assessments based upon how it will play out in cashflows, growth and risk. In truth, is worth remembering key insights from psychology, on how we, as human beings, deal with threats (financial and physical) that we view as existential.

- The first response is denial, an unwillingness to think about catastrophic risks. As someone who lives in a home close to one of California's big earthquake faults, and two blocks from the Pacific Ocean, I can attest to this response, and offer the defense that in its absence, I would wither away from anxiety and fear.

- The second is panic, when the catastrophic risk becomes imminent, where the response is to flee, leaving much of what you have behind.

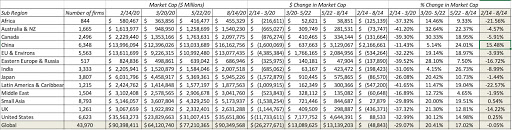

To see this process at work, consider again how the market initially reacted to the COVID crisis in terms of repricing companies that were at the heart of the crisis. Between February 14, 2020 and March 23, 2020, when fear peaked, the sectors most exposed to the pandemic (hospitality, airlines) saw a decimation in their market prices, during that period: