I am not a prolific user of social media platforms, completely inactive on Facebook and a casual lurker on LinkedIn, but I do use Twitter occasionally, and have done so for a long time, with my first tweet in April 2009, making me ancient by Twitter standards. That said, I tweet less than ten times a month and follow only three people (three of my four children) on the platform. I am also fascinated by Elon Musk, and even more so by his most prominent creation, Tesla, and I have valued and written about him and the company multiple times. When Musk made news a little over two weeks ago, with his announcement that he owned a major stake in Twitter, I could not stay away from the story, and what's happened since has only made it more interesting, as it casts light on just Musk and Twitter, but on broader issues of the social and economic value of social media platforms, corporate governance, investing and how politics has become part of almost every discussion.

The Twitter Story

To get a measure of Musk's bid for Twitter, you have to also understand the company's path to its current status. In this section, I will focus on the milestones in the company's history that shape it today, with an eye on how it may affect how this acquisition bid plays out.

Inception to IPO

Twitter was founded in 2006 by Jack Dorsey, Noah Glass, Biz Stone and Evan Williams, and its platform was launched later that year. It succeeded spectacularly in attracting people to its platform, hitting a 100 million users in 2012, and then doubling those numbers again by 2013, when it went public ,with an initial public offering. In a post on this blog on October 5, 2013, I valued Twitter, based on the numbers in its prospectus:

|

| Spreadsheet with valuation |

In keeping with my belief that every valuation tells a story, my IPO valuation of Twitter in October 2013 reflected my story for the company, as a platform with lots of users, that had not yet figured out how to monetize them, but would do so over time. My forecasted revenues for 2023 of $11.2 billion and predicted operating margin of 25% in that year reflected my optimistic take for the company, with substantial reinvestment (in acquisitions and technology) needed along the way (as seen in my reinvestment). A few weeks later, the offering price for Twitter's shares was set at $26, by its bankers, and the stock debuted on November 7, 2013, at $45. In the weeks after, that momentum continued to carry the stock upwards, with the price reaching $73.31 by December 26, 2013.

If the story had ended then, the Twitter story would have been hailed as a success, and Jack Dorsey as a visionary. But the story continues...

The Rise and Fall of Jack Dorsey

In the years since its IPO, the Twitter story has developed in ways that none of its founders and very few of its investors would have predicted. On some measures of user engagement and influence, it has performed better than expected, but in the operating numbers measuring its success as a business, it has lagged, and the market has responded accordingly

Users: Numbers and Engagement

In terms of user numbers, Twitter came into the markets as a success, with 240 million people on its platform in November 2013, at the time of its public offering. In the years since, those user numbers have grown, as can be seen in the chart below:

In keeping with disclosure practices at other user-based companies, in 2017, Twitter also started tracking and reporting the users who were most active on its platform, by looking at daily usage, and counting daily active users (DAU). While total user numbers have leveled off in recent years, albeit with a jump in 2021, the daily active user count has continued to climb.

Over the last decade, the company's platform, and the tweets that show up on it, became a ubiquitous part of news, culture and politics, as politicians used the platform to expand their reach and spread their ideas and celebrities built their personal brands around their followers. Looking at the list of the Twitter persona with the most followers provides some measure of its reach, with a mix of politicians (Barack Obama, Narendra Modi), musicians (Justin Bieber, Katy Perry, Taylor Swift, Ariana Grande), celebrities (Kim Kardashian) and sporting figures (Cristiano Ronaldo). Sprinkled in the list are brands/businesses (YouTube, CNN Breaking News), with millions of followers, though relatively few business people make the list, with Elon Musk being the exception. It is worth noting that many of the people on top follower list tweet rarely, and that behavior is mimicked by many of the users on the platform, many of whom never tweet. The bulk of the tweets on the platform are delivered by a subset of users, with the top 10% of users delivering 80% of the tweets.

While there are multiple reasons that Twitter users come to the platform, the demographics of its platform provides some clues, especially when contrasted with other social media platforms:

|

| Pew Research |

Twitter's user base skews younger, more male, more educated and more liberal than the US population, and especially so, when compared with Facebook, which has the biggest user base.

Revenues, Profits and Stock Prices

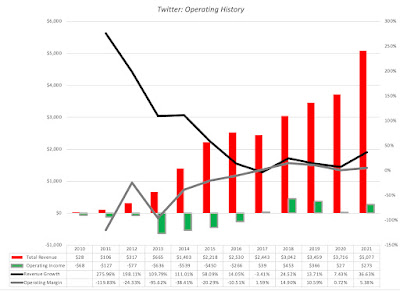

As Twitter user base and influence have grown, there has been one area where it has conspicuously failed, and that is on business metrics. The company's revenues have come primarily from advertising (90%) and while these revenues have grown, they have not kept up with user engagement, as can be seen in the chart below:

In the last few years, revenue growth has flattened, again with the exception of 2021, and while operating margins have finally turned positive in the last five years, there has been no sustained upward movement. To give a measure of Twitter's disappointing performance, note that the company's actual revenues in 2021 amounted to $5.1 billion, well below the $9.6 billion I estimated in 2021 (year 8 in my IPO valuation) as revenues in my IPO valuation of the company in November 2013, and its operating margin, even with generous assumptions on R&D, was 19.02% in 2021, still below my estimate of 19.76% in that year.

The disappointments on the operating metric front has played out in markets, where Twitter's stock price dropped to below IPO levels in 2016 and its performance has lagged its social media counterparts:

|

| Source: Bloomberg |

In fact, Twitter's stock prices did not breach their December 2013 high of $73.31 until February 26, 2021, when the stock peaked at $77.06, before dropping back to 2013 levels again by the end of the year. The company that provides the best contrast to Twitter is Snapchat, another company that I valued at the time of its IPO in February 2017 at $14.4 billion, with a value per share of $10.91. Like Twitter, Snapchat had a rousing debut in the market, rising 40% to hit $24.48 on its first trading day, before falling on hard times, as Instagram undercut its appeal. The stock dropped below $6 in 2019, before mounting a comeback in 2021. While Snap is a younger company than Twitter, a comparison of the operating metrics and user numbers yields interesting results:

Looking at the 2021 numbers, Snap now has more daily active users than Twitter, but delivers less in revenues and is still losing money. That said, the market clearly either sees more value in Snap's story or has more confidence in Snap's management, since there is a wide gap in market capitalizations, with Snap trading at a premium of 60% over Twitter.

Corporate governance

While Twitter can be faulted on many of its actions leading into and after its IPO, there is one area where credit is due to the company. In a period when companies, especially in the tech sector, fixed the corporate governance game in favor of insiders and incumbents, by issuing shares with different voting classes, Twitter stuck to the more traditional model, with equal voting right shares. It is also worth noting that Twitter came into its IPO, with a history of bloodletting at the top, with Jack Dorsey, who led the company at the start, getting pushed aside by Evan Williams, his co-founder, before reclaiming his place at the top. In fact, at the time of its IPO, Twitter's CEO was Dick Costolo, but he was replaced by Dorsey again, a couple of years later. Dorsey's founder status gave him cover, but his ownership stake of the company was not overwhelming enough to stop opposition. As disappointment mounted at the company, the murmuring of discontent became louder among Twitter shareholders, especially since Jack divided his top executive duties across two companies, Twitter and Square, both of which demanded his undivided attention.

The corporate governance issues at Twitter came to a head in 2020, when Elliott Management, an activist hedge fund, purchased a billion dollars of Twitter stock, and demanded changes. While Dorsey was successful in fighting off their demands that he step down, he surprised investors and may company employees when he stepped down in November 2021, claiming that he was leaving of his own volition. That may be true, but it seemed clear that the relationship between Dorsey and his board of directors had ruptured, and that the departure might not have been completely voluntary. As a replacement, the board did stay within the firm in picking a successor, Parag Agrawal, who joined Twitter as a software engineer in 2011 and rose to become Chief Technology Officer in 2017.

The Musk Entree!

It is ironic that the threat to Twitter has come from Elon Musk, who has arguably used its platform to greater effect than perhaps anyone else on it. There are some Twitter personalities who have more followers than Musk, but most of them are either inactive or tweet pablum, but Musk has made Twitter his vehicle for selling both his corporate vision and his products, while engaging in distractions that sometimes frustrate his shareholders. While he has made veiled promises of alternative platforms for expression, it was a surprise to most when he announced on April 4, 2022, that he had acquired a 9.2% stake in the company. Stock prices initially soared on the announcement, but what has followed since has been one of the strangest corporate chronicles that I have ever witnessed, as you can see in the time line below:

This post is being written on April 19, and the only thing that is predictable is that everything is unpredictable, at the moment, and that should come as no surprise, when Musk is involved.

The Value Arguments: Status Quo and Potential

While Musk's acquisition bid is anything but conventional, the gaming that it initiated on the part of Twitter, the target company, and Musk, the potential acquirer, was completely predictable. The company's initial response was that it was worth great deal more than Musk's offering price, and that Twitter shareholders would be receiving too little for their shares if they sold. Musk's response was that the market clearly did not believe that current management could deliver that higher value, and that he would be able to do much better with the platform.

Twitter's argument that Musk was lowballing value, by offering $54.20 per share for the company, and that the company was worth a lot more is not a novel one, and it is heard in almost every hostile acquisition, from target company management. That argument can sometimes be true, since markets can undervalue companies, but is it the case with Twitter? To answer that question, I valued Twitter on April 4, at about the time that Musk announced his 9.2% stake, updating my story to reflect a solid performance from the company in 2021, and with Parag Agrawal, its newly anointed CEO:

|

| Spreadsheet with Twitter Status Quo Value |

Competing Views: The Fight for Twitter

As a company that has lived its entire life on the promise of potential, it should come as no surprise if that is where the next phase of this argument heads. In particular, Twitter's management will claim that the company's platform has the potential to deliver significantly more value, either by changing the business model (and including subscriptions and other revenue sources) or fine tuning the advertising model. On this count, Musk will agree with the argument that Twitter has untapped potential, but counter that he (and only he) can make the changes to Twitter's business model to deliver this potential. In short, investors will get to choose not only between competing visions for Twitter's future, but also who they trust to deliver those visions.

The problem that Twitter's management will face in mounting a case that Twitter is worth more, if it is run differently, is that they have been the custodians of the company for the last decade, and have been unable or unwilling to deliver these changes. Shareholders in Twitter will welcome management's willingness to consider alternative business models, but the timing makes it feel more like a deathbed conversion rather than a well thought through plan. Elon Musk's problem, on the Twitter deal, is a different one. If you think Jack Dorsey was stretching the limits of his time by running two companies, I am not sure how to characterize what Musk will be doing, if he acquires Twitter, since he does have a trillion dollar company to run, in Tesla, not to mention SpaceX, the Boring company and a host of other ventures. In addition, Musk's unpredictability makes it difficult to judge what his end game is, at least with Twitter, since he could do anything from selling his position tomorrow to bulldozing his way through a poison pill, taking Twitter down with him. I know that there are question of how Musk finance the deal and whether he can secure funding, but of all of the impediments to this takeover, those might be the easiest to overcome. The fact that Twitter's stock price has stayed stubbornly below Musk's offering price suggests that investors have their doubts about Musk's true intentions, and whether this deal will go through.

Alternate Endings

No matter what you think about Elon Musk and how his acquisition bid will play out, it is undeniable that he has put Twitter in play here, and that it is likely that the company that emerges from this episode will look different from the company that went into it. In particular, I see four possible outcomes for Twitter:

- Status Quo: It is possible that Twitter wins this round with Musk, and that the poison pill adopted by the board is sufficient to get him to walk away from the deal, perhaps selling his holdings along the way. The existing management go back to their plans for incremental change that they have already put in motion, and hope that the payoffs of higher revenue growth and profitability will unlock share value.

- Musk takes Twitter private: Having spent more than a decade seeing Musk pull off what most market observers would view as impossible, I have learned not to underestimate the man. For Musk to succeed at this point, he has to be able to buy enough shares in a tender offer and/or convince other shareholders to put pressure on the board to remove the poison pill, and allow him to move forward with his plans. The odds are against success, but then again, this is Elon Musk.

- Independent, but with corporate governance changes: Even if Twitter is able to fend off Musk, the way that the company's management and board have handled the deal does not inspire confidence in their ability to run the company. In fact, having gone through five CEOs over Twitter's life, it is worth asking the question whether the dysfunction at the company lies with the board, and not just with the CEO. In this scenario, institutional investors will follow through by pushing for change in the company, translating into new board members and perhaps even a new CEO.

- Someone else acquires Twitter: There may be something to Musk's claim that the changes that are needed to make Twitter a functional business can only be made, if it is taken private. If so, it is the board may be willing to sell the company to someone other than Musk, albeit at a slightly higher price (if for no other reason than to save face). The fact that the buyer may be Silver Lake, a firm that Musk has connections with, or another private equity investor, whose plans for change are similar to Musk's, will mean that Elon Musk will have accomplished much of what he set out to do, without spending $43 billion dollars along the way or having to deal with the distractions that owning Twitter will bring to his other, more valuable, ventures.

Political Markets?

In this discussion, I have deliberately stayed away from the elephant in the room, which is that this is , at its core, a political story, not a financial one. To see why, consider a simple test. If you tell me which side of the political divide you fall on, I am fairly certain that I will be able to guess whether you favor or oppose Musk's takeover bid. As with most things political, you will provide an alternate, more reasoned, argument for why you are for or opposed, but you are deluding yourself, and hypocrisy is rampant on both sides.

- If you are opposed to the deal, and your argument is that billionaires should not control social media platforms, that outrage cannot be selective, and you should be just as upset about Jeff Bezos owning the Washington Post or a George Soros bid for Fox News. If it is Musk's personality that you feel is what makes him an unsuitable owner, I wonder whether we should be requiring full personality tests of the owners of other media companies.

- If you are for the deal, and it is because you want Twitter to be a bastion of free speech, it is worth remembering that every social media platform is involved in some degree of censoring, for legal reasons and self preservation. It should also be noted that while those disaffected with Twitter have attempted to build their own social media platforms, they still get far more mileage from their presence on Twitter than from their posts on alternate platforms, and the complaints about Twitter not being balanced seem to end up being on Twitter.