It was an interesting year for interest rates in the United States, one in which we got more evidence on the limited power that central banks have to alter the trajectory of market interest rates. We started 2024 with the consensus wisdom that rates would drop during the year, driven by expectations of rate cuts from the Fed. The Fed did keep its end of the bargain, cutting the Fed Funds rate three times during the course of 2024, but the bond markets did not stick with the script, and market interest rates rose during the course of the year. In this post, I will begin by looking at movements in treasury rates, across maturities, during 2024, and the resultant shifts in yield curves. I will follow up by examining changes in corporate bond rates, across the default ratings spectrum, trying to get a measure of how the price of risk in bond markets changed during 2024.

Treasury Rates in 2024

Coming into 2024, interest rates had taken a rollicking ride, surging in 2022, as inflation made its come back, before settling in 2023. At the start of 2024, the ten-year treasury rate stood at 3.88%, unchanged from its level a year prior, but the 3-month treasury bill rate had climbed to 5.40%. In the chart below, we look the movement of treasury rates (across maturities) during the course of 2024:

|

| Download daily data |

During the course of 2024, long term treasury rates climbed in the first half of the year, and dropped in the third quarter, before reversing course and increasing in the fourth quarter, with the 10-year rate ending the year at 4.58%, 0.70% higher than at the start of the year. The 3-month treasury barely budged in the first half of 2024, declined in the third quarter, and diverged from long term rates and continued its decline in the last quarter, to end the year at 4.37%, down 1.03% from the start of the year. I have highlighted the three Fed rate actions, all cuts to the Fed Funds rate, on the chart, and while I will come back to this later in this post, market rates rose after all three.

The divergence between short term and long term rates played out in the yield curve, which started 2024, with a downward slope, but flattened out over the course of the year:

|

| Download daily data |

The Drivers of Interest Rates

Over the last two decades, for better or worse, we (as investors, consumers and even economics) seem to have come to accept as a truism the notion that central banks set interest rates. Thus, the answer to questions about past interest rate movements (the low rates between 2008 and 2021, the spike in rates in 2022) as well as to where interest rates will go in the future has been to look to central banking smoke signals and guidance. In this section, I will argue that the interest rates ultimately are driven by macro fundamentals, and that the power of central banks comes from preferential access to data about these fundamentals, their capacity to alter those fundamentals (in good and bad ways) and the credibility that they have to stay the course.

Inflation, Real Growth and Intrinsic Riskfree Rates

It is worth noting at the outset that interest rates on borrowing pre-date central banks (the Fed came into being in 1913, whereas bond markets trace their history back to the 1600s), and that lenders and borrowers set rates based upon fundamentals that relate specifically to what the former need to earn to cover expected inflation and default risk, while earning a rate of return for deferring current consumption (a real interest rate). If you set the abstractions aside, and remove default risk from consideration (because the borrower is default-free), a riskfree interest rate in nominal terms can be viewed, in its simplified form, as the sum of the expected inflation rate and an expected real interest rate:

Nominal interest rate = Expected inflation + Expected real interest rate

This equation, titled the Fisher Equation, is often part of an introductory economics class, and is often quickly forgotten as you get introduced to more complex (and seemingly powerful) monetary economics lessons. That is a pity, since so much of misunderstanding of interest rates stems from forgetting this equation. I use this equation to derive what I call an "intrinsic riskfree rate", with two simplifying assumptions:

- Expected inflation: I use the current year's inflation rate as a proxy for expected inflation. Clearly, this is simplistic, since you can have unusual events during a year that cause inflation in that year to spike. (In an alternate calculation, I use an average inflation rate over the last ten years as the expected inflation rate.)

- Expected real interest rate: In the last two decades, we have been able to observe a real interest rate, at least in the US, using inflation-protected treasury bonds(TIPs). Since I am trying to estimate an intrinsic real interest rate, I use the growth rate in real GDP as my proxy for the real interest rate. That is clearly a stretch when it comes to year-to-year movements, but in the long term, the two should converge.

|

| Download data |

While the match is not perfect, the link between the two is undeniable, and the intrinsic riskfree rate calculations yield results that help counter the stories about how it is the Fed that kept rates low between 2008 and 2021, and caused them to spike in 2022.

- While it is true that the Fed became more active (in terms of bond buying, in their quantitative easing phase) in the bond market in the last decade, the low treasury rates between 2009 and 2020 were driven primarily by low inflation and anemic real growth. Put simply, with or without the Fed, rates would have been low during the period.

- In 2022, the rise in rates was almost entirely driven by rising inflation expectations, with the Fed racing to keep up with that market sentiment. In fact, since 2022, it is the market that seems to be leading the Fed, not the other way around.

The Fed Effect

I am not suggesting that central banks don't matter or that they do not affect interest rates, because that would be an overreach, but the questions that I would like to address are about how much of an impact central banks have, and through what channels. To the first question of how much of an impact, I started by looking at the one rate that the Fed does control, the Fed Funds rate, an overnight interbank borrowing rate that nevertheless has resonance for the rest of the market. To get a measure of how the Fed Funds rate has evolved over time, take a look at what the rate has done between 1954 and 2024:

As you can see the Fed Funds was effectively zero for a long stretch in the last decade, but has clearly spiked in the last two years. If the Fed sets rates story is right, changes in these rates should cause market set rates to change in the aftermath, and in the graph below, I look at monthly movements in the Fed Funds rate and two treasury rates - the 3-month T.Bill rate and the 10-year T.Bond rate.

- Information: It is true that the Fed collects substantial data on consumer and business behavior that it can use to make more reasoned judgments about where inflation and real growth are headed than the rest of the market, and its actions often are viewed as a signal of that information. Thus, an unexpected increase in the Fed Funds rate may signal that the Fed sees higher inflation than the market perceives at the moment, and a big drop in the Fed Funds rates may indicate that it sees the economy weakening at a time when the market may be unaware.

- Central bank credibility: Implicit in the signaling argument is the belief that the central bank is serious in its intent to keep inflation in check, and that is has enough independence from the government to be able to act accordingly. A central bank that is viewed as a tool for the government will very quickly lose its capacity to affect interest rates, since the market will tend to assume other motives (than fighting inflation) for rate cuts or raises. In fact, a central bank that lowers rates, in the face of high and rising inflation, because it is the politically expedient thing to do may find that market interest move up in response, rather than down.

- Interest rate level: If the primary mechanism for central banks signaling intent remains the Fed Funds rate (or its equivalent in other markets), with rate rises indicating that the economy/inflation is overheating and rate cuts suggesting the opposite, there is an inherent problem that central banks face, if interest rates fall towards zero. The signaling becomes one sided i.e., rates can be raised to put the economy in check, but there is not much room to cut rates. This, of course, is exactly what the Japanese central bank has faced for three decades, and European and US banks in the last decade, reducing their signal power.

Corporate Bond Rates in 2024

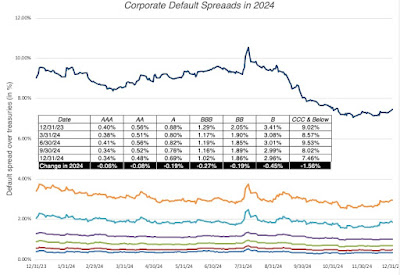

The corporate bond market gets less attention that the treasury bond market, partly because rates in that market are very much driven by what happens in the treasury market. Last year, as the treasury bond rate rose from 3.88% to 4.58%, it should come as no surprise that corporate bond rates rose as well, but there is information in the rate differences between the two markets. That rate difference, of course, is the default spread, and it will vary across different corporate bonds, based almost entirely on perceived default risk.

Default spread = Corporate bond rate - Treasury bond rate on bond of equal maturity

Using bond ratings as measures of default risk, and computing the default spreads for each ratings class, I captured the journey of default spreads during 2024:

The decline of fear in corporate bond markets can be captured on another dimension as well, which is in bond issuances, especially by companies that face high default risk. In the graph below, I look at corporate bond issuance in 2024, broken down into investment grade (BBB or higher) and high yield (less than BBB).

Note that high yield issuances which spiked in 2020 and 2021, peak greed years, almost disappeared in 2022. They made a mild comeback in 2023 and that recovery continued in 2024.

Finally, as companies adjust to a new interest rate environment, where short terms rates are no longer close to zero and long term rates have moved up significantly from the lows they hit before 2022, there are two other big shifts that have occurred, and the table below captures those shifts:

YouTube

- Data Update 1 for 2025: The Draw (and Danger) of Data!

- Data Update 2 for 2025: The Party continued for US Equities

- Data Update 3 for 2025: The times they are a'changin'!

- Data Update 4 for 2025: Interest Rates, Inflation and Central Banks!

- Data Update 5 for 2025: It's a small world, after all!

- Data Update 6 for 2025: From Macro to Micro - The Hurdle Rate Question!

- Data Update 7 for 2025: The End Game in Business!

- Data Update 8 for 2025: Debt, Taxes and Default - An Unholy Trifecta!

- Data Update 9 for 2025: Dividend Policy - Inertia and Me-tooism Rule!

Data Links

.jpeg)

.jpeg)